Muncie Political History Facebook Archive

Muncie's Chapter of the Workingmen's Party

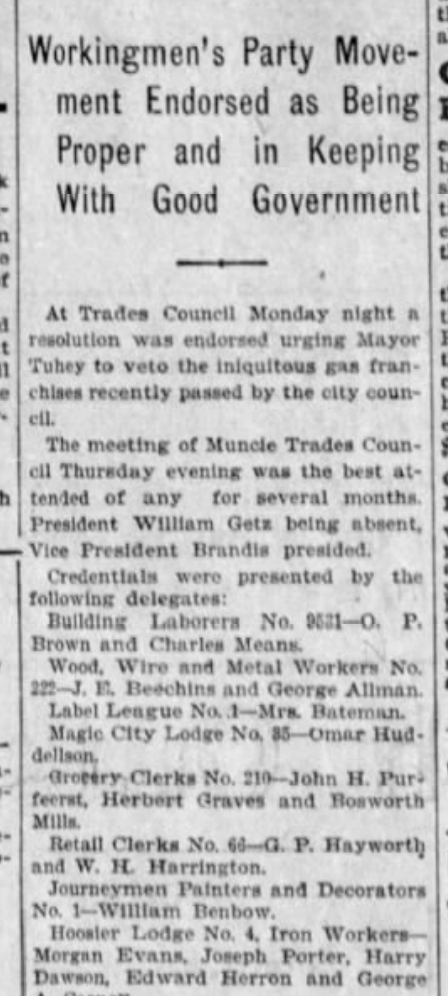

The early 20th century in the United States saw all kinds of reform parties, and Muncie, Indiana saw plenty of these. One of which being the Workingmen’s Party, a long gone labor movement that spawned up again in the city in 1902.

The party on a national level has significant importance to the state of Indiana. Robert Owen’s son, also named Robert, formed the Workingmen’s Party in New York in 1829. His father created the first socialist utopia in New Harmony, which influenced many “Owenite” communities throughout the United States. Long after this in 1902, there would be a full ticket for the party in Muncie. What made this particularly interesting is the fact that the Workingmen’s Party officially ended in 1878, yet a new chapter was emerging exclusively in Muncie decades later. While it’s hard to tell why the Workingmen’s Party suddenly became a thing in Muncie, connection can be made to the People’s Party movement from a decade prior. People’s Party followers, or “populists,” circulated copies of the New York magazine “The People” within town. Started by the Socialist Labor Party of America in 1891, the same organization was called the Workingmen’s Party of the United States until 1876 when they decided to rename it.

In Muncie’s 1902 race for mayor, city council seats, and the ticket included Frank J. Lafferty, who won a seat in City Council in 1900, running for mayor on the Workingmen’s ticket. He was a glass worker at Ball Bros factory and the national president of the Green Glass Pressers’ League. The party also had Henry Cawley running as county clerk, George Derrick running for treasurer, and several more candidates for every city council seat. Lafferty ran unopposed in the party and members shouted their support for his nomination after his speech during a meeting.

In the end the only party member to win was Joseph Porter from 6th Ward. Lafferty only received 899 votes compared to Republican Charles Sherritts 1,862 and Democrat Harry Wysors 1,399. It’s still a mystery as to why the party formed in exclusively in Muncie long after it fizzled out in the 1870’s, however I’d like to give thanks to Chris Flook for emailing me newspaper clippings related to this.

A Rival Paper to The Post-Democrat

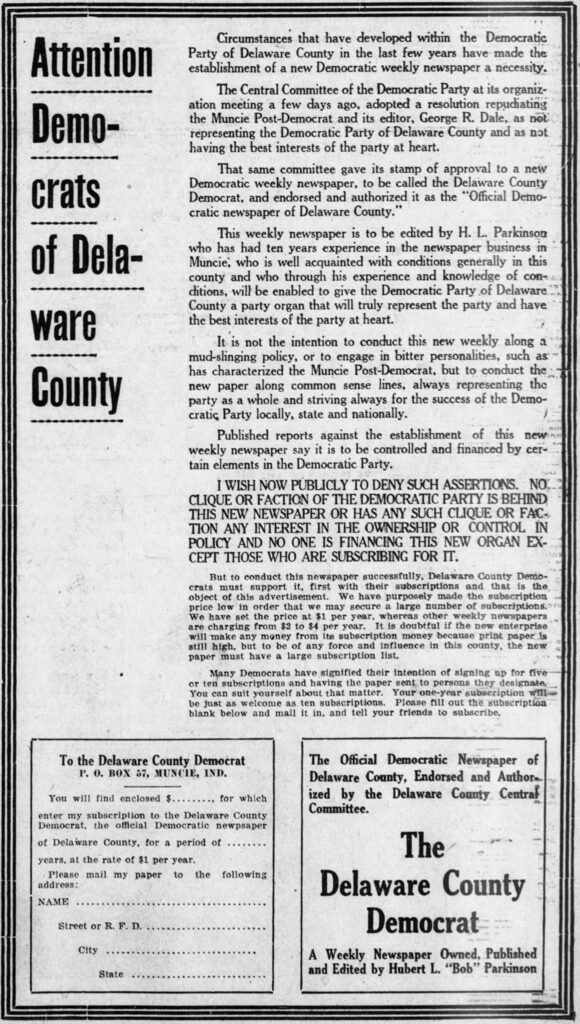

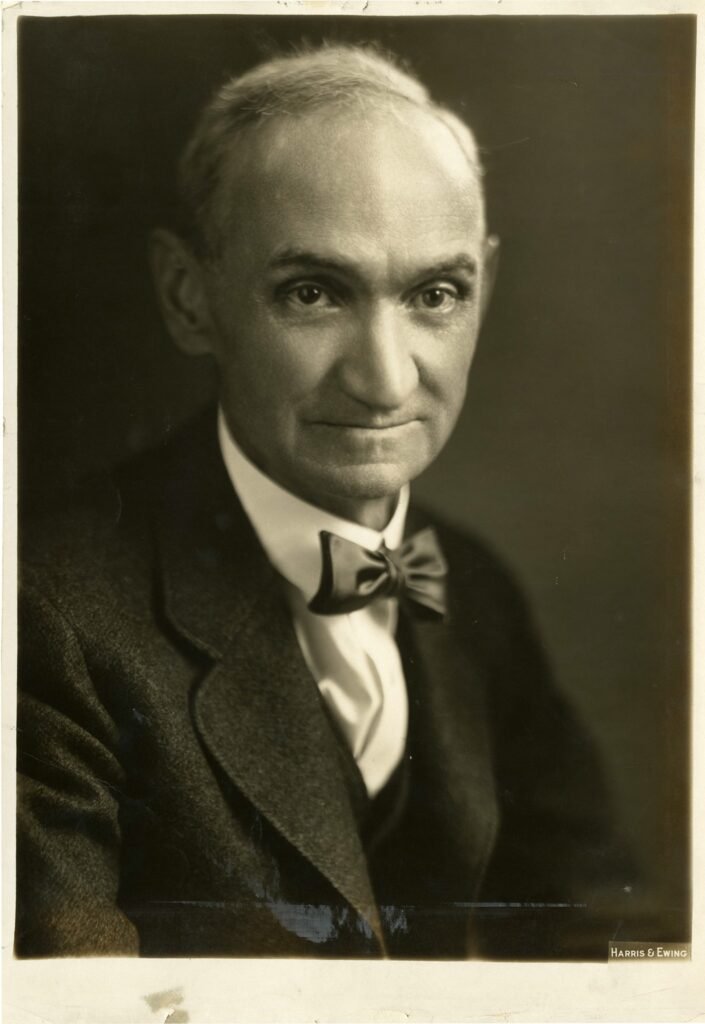

In the 1920s, Muncie democrats were divided because of the corrupt Bunch administration and the dissident newspaper ran by George R. Dale. And in 1922, a rival paper by the Delaware County Democrats was put into fruition.

Weeks ago, we covered the political scandal of Rollin H. Bunch, and one person who had a big voice in the aftermath was editor and eventual mayor George R. Dale. Dale was known for stirring lots of controversy, early on for both attacking bootleggers and defending labor then later in the 20s for attacking the KKK. Down the road we will be covering his fight against the Klan, but this week we will look at his fight against his own political party. Because all we have is newspaper clippings, we don’t have the full story of the rivalry. And because the new democratic paper was never made, Dales editorials in the Post-Democrat drown out the little written by Democratic party leaders.

Dale got started in the newspaper business in the early 1890’s, when he quit his paper mill job at the age of twenty-one and started the Hartford City Times, The Montpelier Call, Hartford City Journal, and eventually the Muncie Post and Post-Democrat when he moved here in 1915. Rollin H. Bunch, mayor at the time, hired Dale as an editor for his own paper, the Muncie Post, in 1915. The two had a falling out after Bunch was convicted of mail fraud and went to prison in Georgia for eighteen months, thus discontinuing the Muncie Post in 1918 and later the creation of the Post-Democrat in 1921. Dales editorials railed against city officials by calling them crooks and hypocrites, which made Dale lose support from democrats (the opposition to the Post-Democrat was also because the paper didn’t support Bunch’s run for mayor). They argued that the paper, or the views of Dale himself anyway, were not representative of how democrats in the county felt. Given how temperamental Dale often was it comes to no surprise that other democrats could feel this way. On May 6th, 1922, the Democrat County Convention held what was meant to be an ordinary meeting. But the warring factions of the party faced off, and in one instance Committeeman Harry Stout shouted “it is time for the committeemen to take charge of the party” which then provoked a shouting match between him and Billy Finan. At the convention, a resolution was declared that stated the party was not represented by a truly Democratic newspaper nor that the paper has the best interests of the party at heart, and declared that by June 1st, 1922, Hubert L. Parkinson will establish a new paper. Party members wrote this in the Evening Press: “It is not the intention to conduct this new weekly along a mud-slinging policy, or to engage in bitter personalities, such has characterized the Muncie Post-Democrat, but to conduct the new paper along common sense lines, always representing the party as a whole and striving always for the success of the Democratic Party locally, state and nationally.”

The rival newspaper was going to be edited by Hubert L. Parkinson and was supported by Bunch, Obed Kilgore, Billy Finan and others. The creation of the paper was delayed before it ultimately never happened, thus only one democratic newspaper existed in Muncie in that period.

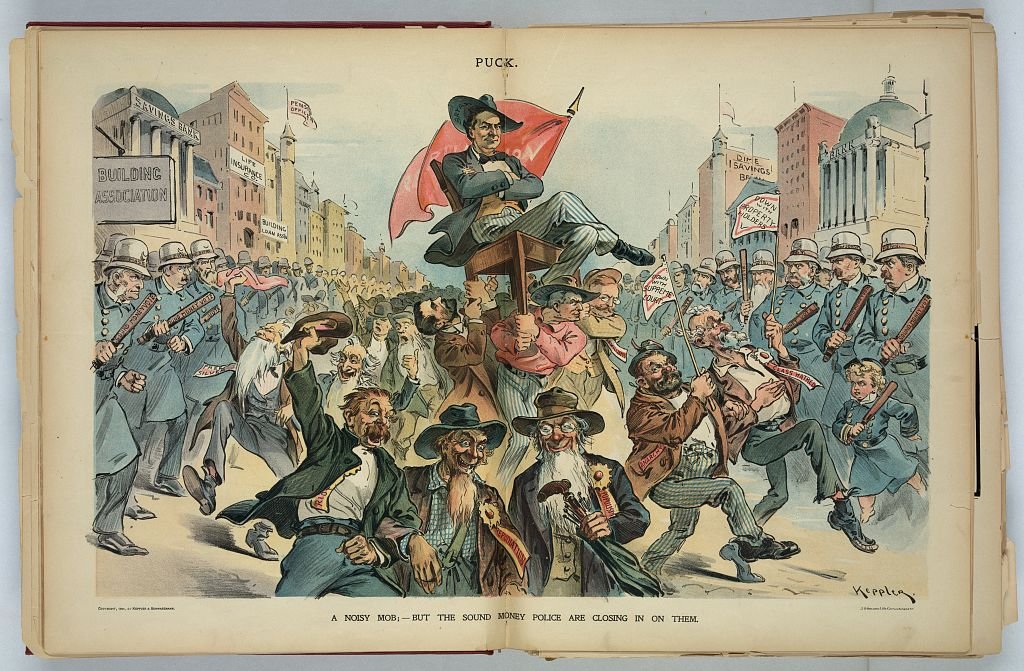

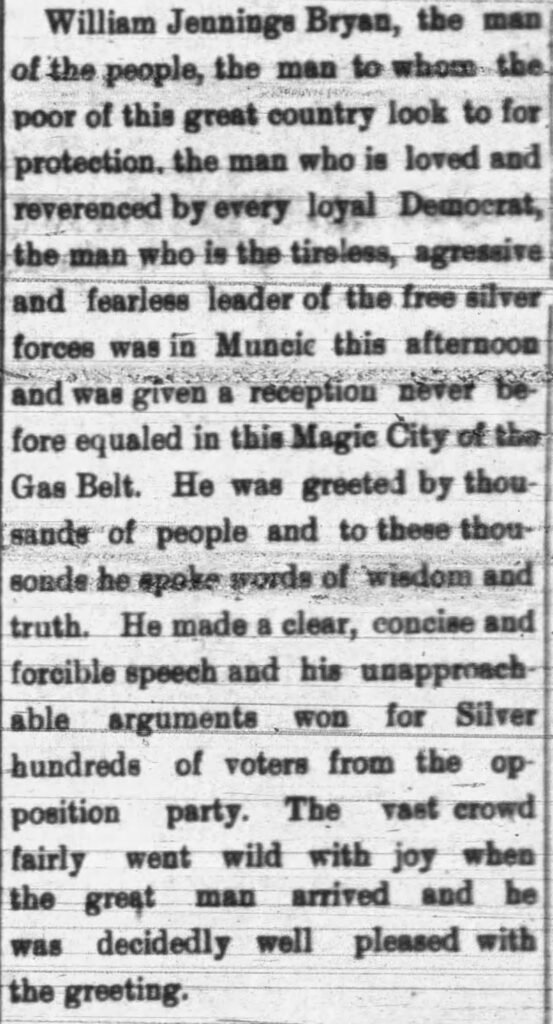

William Jennings Bryan and Populism in Muncie

On October 21st, 1896, presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan campaigned here in Muncie. The next week, well known Indiana politician Eugene Debs also gave a speech to support Bryan for president.

William Jennings Bryan was a presidential candidate three elections in a row, not only because of loyal Democrats but because of the Peoples Party. The Peoples Party, who’s followers deemed themselves as populists, advocated for greater regulation of currency. In addition, they also advocated for increased minimum wage, nationalizing railroads, and getting rid of the gold standard. According to records, there was a Peoples Party present in Muncie and possibly a Greenback Party in the 1870s (a precursor to the Peoples Party).

Years prior to this election in 1891, Arthur Brady became mayor partly thanks to the People’s Party movement. A fusion electorate existed at the time, which allowed Arthur Brady to not only be endorsed by but also placed on the ticket for the People’s Party along with the Democratic ticket. Clearly the enthusiasm for the Peoples Party followed into 1896, when presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan and Terre Haute socialist Eugene Debs made their visits here. On top of all of this happening, former president Benjamin Harrison visited the same day to endorse William McKinley. Today in Muncie it would seem impossible for so many famous politicians to all make appearances, let alone just one presidential candidate. When then-candidate Barack Obama campaigned here in 2008, it was a real shocker. Though Muncie was booming in that era and was coined the “Magic City.” When Bryan visited on October 21st, thousands of people stormed his private car between Mulberry and Walnut street. He was popular among the huge crowd, except for the town industrialists who booed and heckled him during his speech. Just over a week later was when Debs visited, and in his speech he said that the platform of McKinley stands “for Great Britain and while the Bryan platform is for the United States.”

Bryan made his last run for president in 1900, and that year he was also against William McKinley. The support for Bryan in Muncie is just one part of the ongoing labor movements in Muncie for the next few decades, which I will continue to cover in the next couple of weeks.

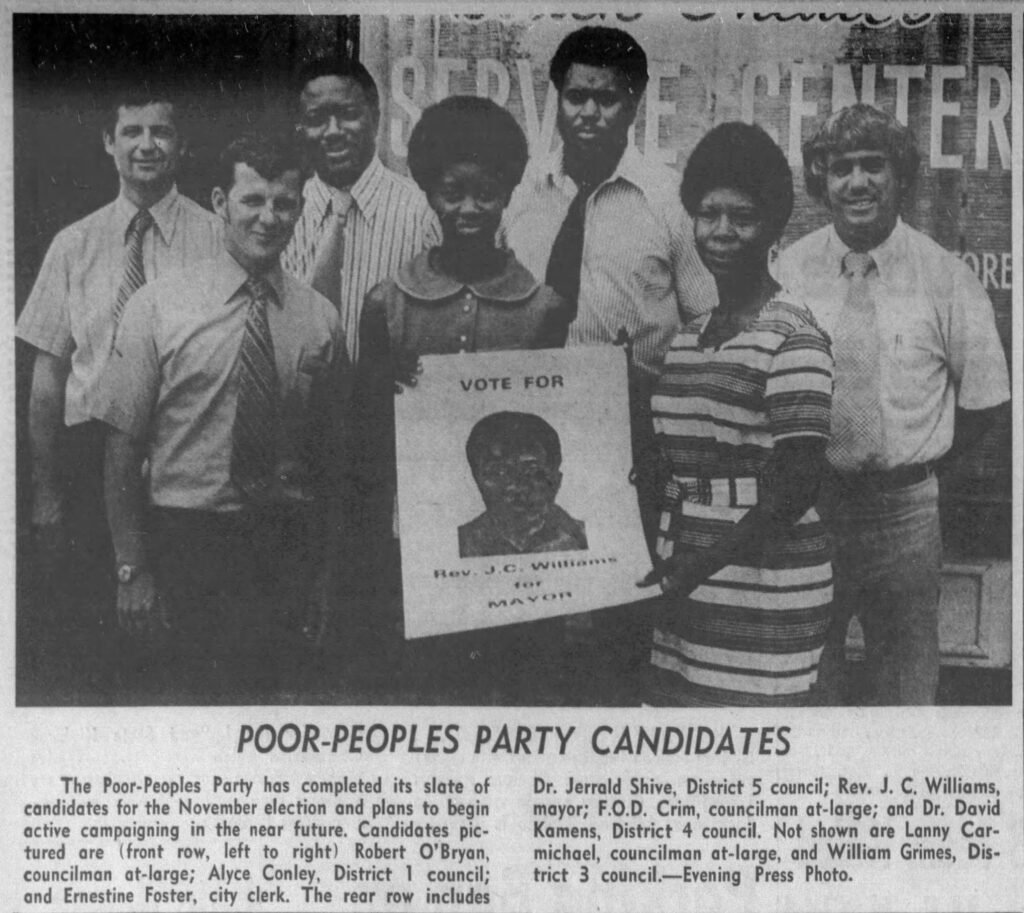

Muncie's Chapter of the Poor Peoples Campaign in 1971

The Poor Peoples Campaign that existed in the late 60’s had a big impact here in Muncie. In 1971, supporters of the movement rallied behind a full ticket of candidates who represented the Muncie communities most disenfranchised citizens.

The Poor People’s Campaign was not only Martin Luther King Jr’s final project, it was also his most ambitious. As president of the Sothern Christian Leadership Conference, King proposed this militant project in 1967 with the goal of taking on racial discrimination in the South while challenging the harsh economic inequality that existed, two issues that King believed were closely connected. The PPCs accomplishments included the March on Washington with tens of thousands of supporters in 1968, creating food programs to feed the one thousand neediest counties in the country, and getting the federal government to approve rent subsidies and home ownership assistance for the poor. The PPC was effective in promoting inclusivity of all races, encompassing support from many different religious denominations, and broadly mobilizing communities across the country to influence both federal and public policy.

So how did this effect Muncie? The result of Muncie’s mayoral election of 1967, in which Paul J. Cooley won his first term, was made possible by minorities, poor individuals, and organized labor. Despite this, these groups were not satisfied with the Cooley administrations lack of representation for their needs. Like MLK, these leaders in Muncie believed that economic issues were directly linked with racism, and thus they decided to start their own chapter of the PPC. There are records that show the PPC being present in the city as early as ’67 by Ball State students, however it really took off in the next election in ’71. That was when the Muncie branch of the PPC started its own political party with a full ticket running for all positions. PPC organizations throughout the country did not run candidates, however Muncie’s chapter is unique for having done it. Running for mayor on the ticket was Reverend J.C Williams, a minister at Trinity United Methodist Church and a member of the Collective Coalition of Concerned Clergy. Over the next few months more candidates including Ernestine Foster, Robert O’Bryan, Dr. Jerald Shives, and several others ran on the ticket.

In the end, Cooley won the election and none of the PPP candidates won. Williams performed better than any other third party mayoral candidate in city’s history, the last big attempt at a third party before then took place in 1913. Another accomplishment from the election: Dan Kelly, a Black man running as a Democratic Councilman in the sixth district, won reelection as did James Johnson for Council-At-Large.

Gerald Chapman

One of the most notorious bank robbers in American history, Gerald Chapman, was arrested right here in Muncie. This brought national fame to the city, a considerable amount of it since this was before the first Middletown book.

Gerald Chapman, otherwise known as the Gentleman Bandit, was a famous bank robber before the times of John Dillinger or Bonnie and Clyde. He became “Public Enemy Number One” after his killing of a policeman in Connecticut, which put him on the run until he was captured on January 18th, 1925. His arrest was in Muncie, and the officers responsible for the arrest included Captain Fred Puckett, Detective Harry Brown, Detective Samuel Goodpastor and Officer Merlyn Collins. Afterwards he was sent to Connecticut where he was given the death penalty. For his role in the arrest, Fred Puckett’s 1943 obituary was placed in the Chicago Tribune, stating he “recognized Chapman on a street in the residential section and ordered him to surrender. The outlaw drew a pistol, but Puckett overpowered and disarmed him.” Puckett first started serving around the beginning of the 20th century, and in 1914 became “chief of detectives,” a new position created when Rollin H. Bunch became mayor that year. Puckett was later demoted when John C. Hampton became mayor in 1926, along with detective Harry Brown and many others. It is unknown exactly why they were both demoted despite making an arrest that brought national fame to Muncie. Author Carrolyle Frank believed that Puckett’s demotion was likely related to him being a Democrat serving during Hamptons administration. Though in 1928 he was elected sheriff of Delaware County. A similar thing happened in the next administration when mayor George Dale fired thirty-nine of the forty-two members of the police force and appointing the other three men responsible for Gerald Chapman arrest (Brown, Collins and Goodpastor).

It’s not known exact what Chapman was doing in Muncie. One reason would be the fact that Muncie was an ideal place for crime, considering it was a big place for gambling and bootlegging at the time. Another reason being his association with a local resident. In the 2015 book by Keith Roysdon and Douglass Walker, “Wicked Muncie,” the arrest of Chapman is presented as a longer saga. It’s likely that the person responsible for bringing Chapman and his crew here was Charles ‘One-Arm” Wolf. Wolf had a court case in 1927 which would bring back attention not only to the Chapman saga but to Judge Clarence Dearth. Dearth was voted out of office by the House of Representatives, thanks to a petition by Muncie citizens, and he received another accusation of violating rules when prospective jurors for the Wolf trial were selected.

After his execution the next year, two songs were written about the infamous robber. One by Arthur Fields and the other, “The Story of Gerald Chapman,” by Carl Conner.

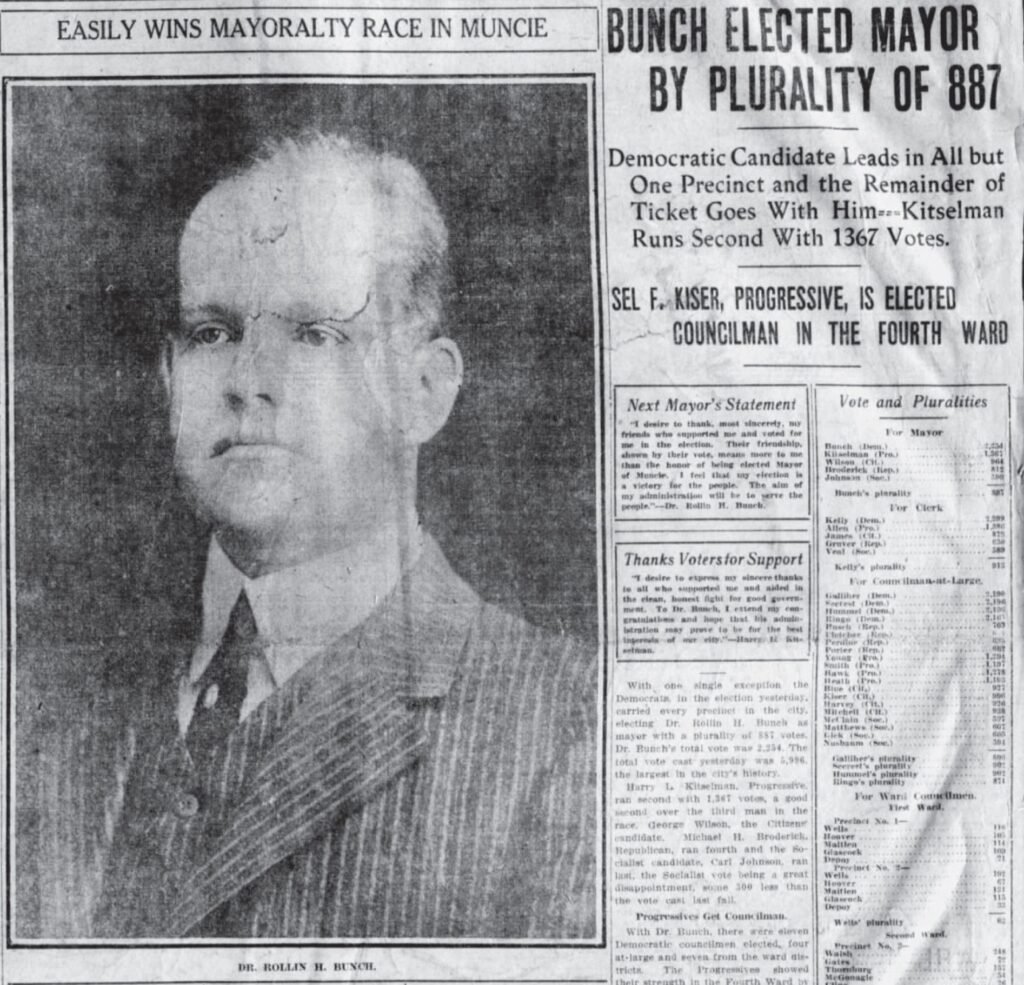

The Imprisonment of Rollin Bunch

Corruption has been a problem in Muncie for quite a while. And with former mayor Dennis Tyler now pleading guilty to charges of theft, its more relevant than ever to bring up city corruption from the past.

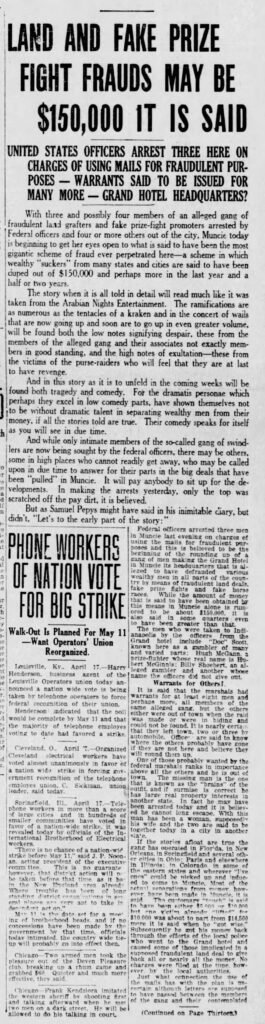

One very notable case of corruption in Muncie was in 1919, when mayor Rollin H. Bunch was arrested for mail fraud. Bunch was Muncie’s political maverick in that era, who was elected as a member of city council in 1909 and mayor on three different occasions. Even after his third term he ran again for every election until his death in 1948, and this page posted about his first election in 1913. Although he was considered a reformist and champion of pro-labor values, Bunch also used power politics to get elected. Earlier In 1915 Bunch and others would be indicted with “having solicited and accepted bribes from blind tiger operators, gambling house keepers and from madams of houses of ill-fame.” But this would be nothing compared to what happened during his second term when he was arrested for mail fraud and was sentenced to two years at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary in Georgia.

In 1919 it was reported that Bunch and many others were committing mail fraud. According to the Evening Press, “they were charged with using the mail to defraud a growing group of wealthy men from around the country by means of bogus real estate transactions, prize fights, and horse races. According to the earliest newspaper accounts, the amount stolen was around $150,000 (this would eventually swell to over half a million), and the gang was reputedly operating in Florida, Louisiana, Illinois, Ohio, and Colorado, in addition to Indiana.” Bunch resigned on December 1st, 1919 and went to the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary in Atlanta, Georgia a week later. During his time there, which ended up only lasting eighteen months, John R. Kelly served as mayor and Bunch kept in contact with many people in Muncie. According to a close friend of Bunch, Abe Falls, he was allowed to stay in a small house away from the prison cells and was friendly with many of the inmates and guards. For a while after the mail fraud incident, it was impossible for a democrat to win any position in Muncie or throughout Indiana. This was also because of the popularity of the KKK, which will be covered in an upcoming post, which was predominately a republican organization and stopped democrats from winning offices.

Even 100 years ago, Muncie was considered a highly corrupt city in Indiana. It’s unfortunate that these activities continue in the current day within our municipal government.

The 1968 Southside High School Riot

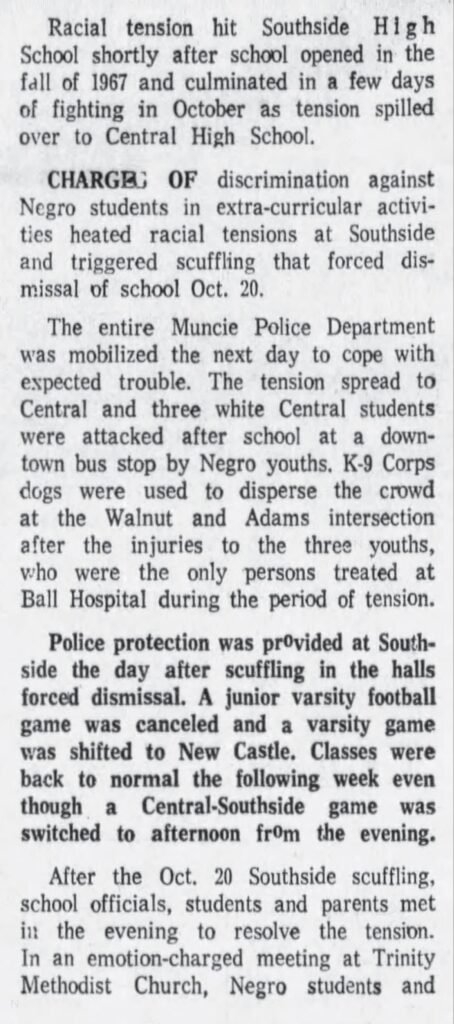

When a riot at Southside High School broke out in 1967, which happened due to racial exclusion being present at the school, it became a big event and marked important change for civil rights in Muncie.

At Southside High School, there was active exclusion of Black students from school activities. There was also the confederate flag being used as the school’s symbol, one Black student said the flag “is as offensive to us as a swastika flying would be to the Jewish students attending this school.” As a result of the frustration created, a big fight broke out on October 19th, 1967. Several people were injured, including a police officer who broke an arm and multiple students who were hospitalized. Prior to this, Black students expressed their feelings of being excluded from their school to the faculty and prominent leaders in the Muncie community. Southside senior Ernestine Cooper said in The Star “teachers help all students, including Negroes, in classes, but we don’t get a fair shake in representation in extra-curricular activities. We shouldn’t be let into activities just because we are Negroes, but because we are capable in those areas and want to help the school. We don’t get credit now for what we can do.” Cooper was the leader of multiple students who met with the Muncie Human Rights Commission days prior to the incident.

One well known civil rights leader that spoke about this event was Hurley Goodall. He had this to say in The Star: “Discrimination in extracurricular activities and the use of the confederate flag as Southside’s symbol combined with the rising violence in protest movements throughout the nation fueled resentment. As it boiled over in the fall of 1967, administrators had an opportunity to address the problems and start an active dialog among the students and teachers, yet their job was incomplete because trouble resurfaced.” The Muncie HRC suggested hiring more Black faculty members, improving school-parent relationships, and conducting in-service training programs for teachers. These actions weren’t taken by the school for a while, but years later the confederate flag would stop being flown. More events followed after, including another fight in January of 1968 and a hearing by the Indiana Civil Rights Commission in March.

Many years later in 2001, Ball State theater students wrote and performed a play about the incident, however when presenting the script to a group of Muncie residents, including people who witnessed the fight happen at the school, many considered the play to be exploitive. Down the road more effort was made to integrate schools in Muncie, though it took years for that change to happen.

The 1938 Mayoral Election

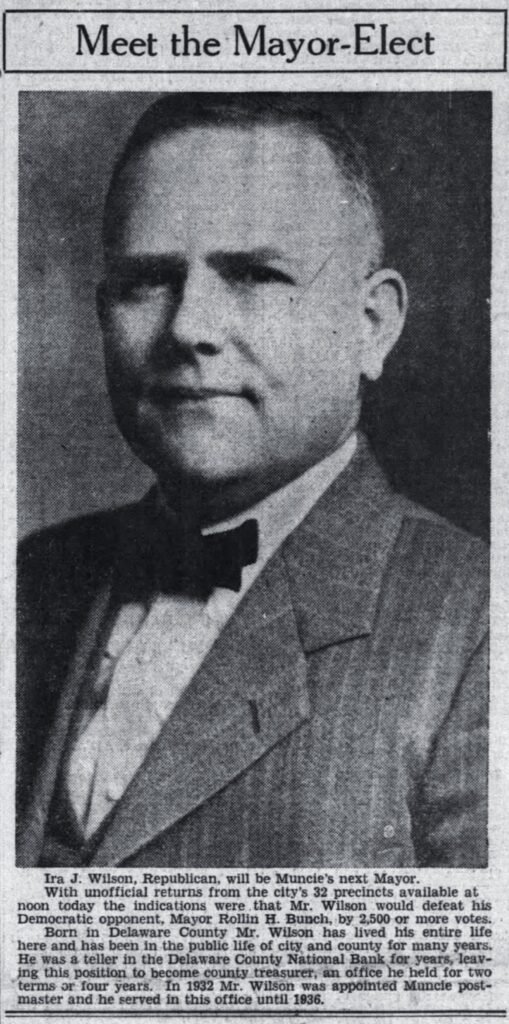

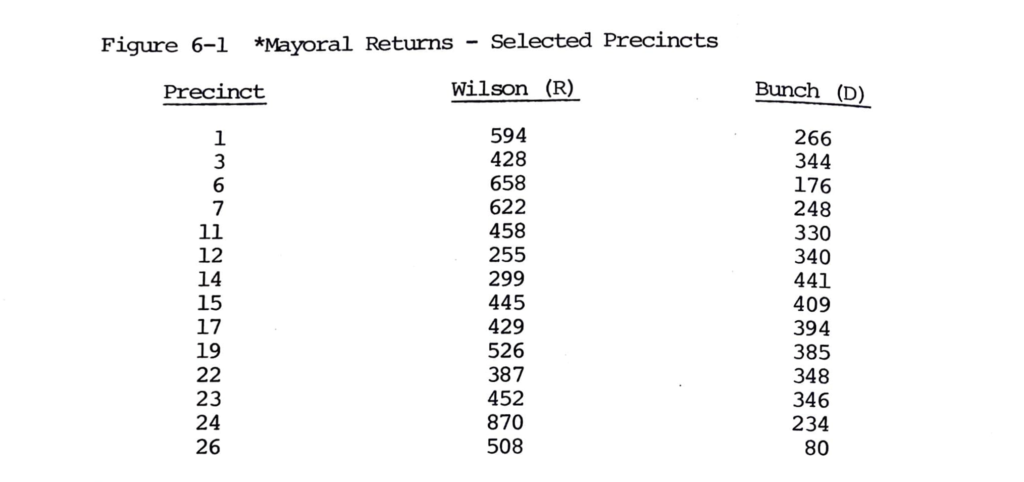

One of our many fascinating elections was that of 1938’s mayoral election, in which Ira J. Wilson beat previous mayor Rollin H. Bunch by 4,730 votes. The election showed a swap of the appeal for each party and brought Republican control back to the city.

In this era of Muncie politics, it was typically the Democrats that carried loyal Southside support. Namely Rollin H. Bunch, the urban populist, and George R. Dale who was a liberal reformer. Naturally, the Republicans were the party that embraced big business, and therefore gained support from the wealthy Northside of the City. This however wasn’t the case in the 1938 election, one that Thomas Moran, who wrote “Pendulum Politics: The Political System of Muncie,” called the most overlooked up until 1975. Republican candidate Ira J. Wilson was a banker and a well-liked resident of Muncie, who also served as county treasurer and postmaster.

His opponent was Rollin H. Bunch, who was a popular mayor in the 1910s up until being charged for mail fraud, and his term in the 30s can be described as his “big business” term. As Thomas Buchanan suggested in his dissertation on Bunch, it could have been several things including the anti-Bunch faction of the Democratic party that caused his loss. The fervently angry anti-Bunch Democrat Fred De Elliot claimed that Bunch let go of his promises to the Southside, and despite the claims by Bunch he believed Wilson would continue federal projects. Clearly Wilson, who professed to being a supporter of the working class residents, took from the loyal Southside support that Bunch gained for decades. It was the Southeastern precincts showed the complete opposite results from the previous election, and the first time that many Southside precincts voted in droves for a Republican since 1925. Interesting fact: Willard J. Daniel, an active socialist writer in the 1910s and a street commissioner during both Dale’s term and Bunch’s third term, also campaigned for Ira Wilson’s campaign by giving numerous speeches. It would seem odd considering he appeared to align himself more with Democrats, however Daniel was “always on the side of the working man” according to a friend who spoke at his funeral.

Wilson declined to run again in 1942. With the last two mayoral elections being won by Democrats, Wilson’s victory marked re-organization for the GOP in Muncie as the only Democrat to win was Ora T. Shroyer as 2nd district councilman.

Muncie's Response to the 1918 Pandemic

The influenza pandemic in 1918 was an event that was very similar to the pandemic we’re in now. Nationwide, and specifically in Muncie, it was hard for public officials to handle the outbreak and keep residents safe.

Muncie was no exception to the impact of the pandemic, which infected 500 million and killed 50 million worldwide. Throughout several months that started in 1918 the death rate was low in November, spiked in December, and grew even more in March the next year. Residents of Muncie didn’t entirely know how to handle what was happening. In an Evening Press article, three different Muncie physicians were asked about their opinion on the flu and each one gave a different answer. One said masks should be worn yet another physician said they’re useless, which made the people of Muncie outright confused as to what they should be doing in reaction to the situation, much like the rest of the country. The irresponsibility regarding health and safety happened largely because throughout Indiana, mask regulations were inconsistent, contested, and controversial. Other than Indianapolis and Fort Wayne, most cities either didn’t enforce masks or, like Muncie, only recommended them.

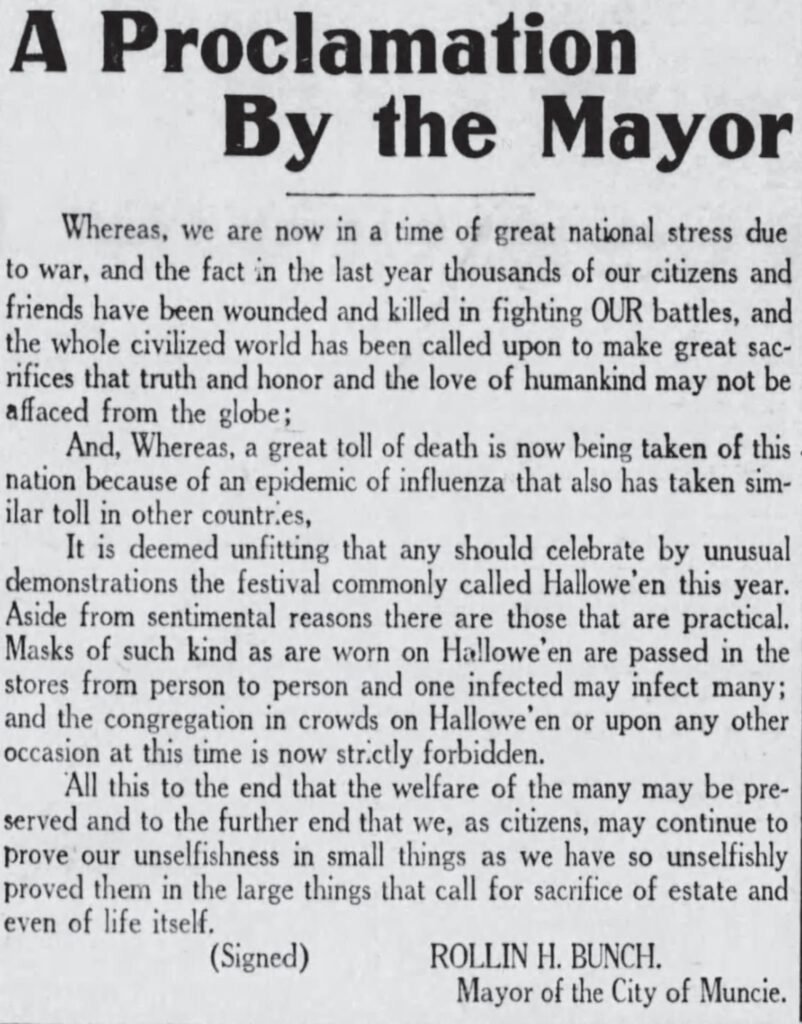

In the same week as Halloween that year, mayor Rollin H. Bunch warned the people of Muncie not to celebrate. In the proclamation from October 24th, he tells Munsonians that for practical reasons people should not celebrate the holiday due to more potential infections. He ends his proclamation by saying “all this to the end that the welfare of the many may be preserved and to the further end that we, as citizens, may continue to prove our unselfishness in small things as we have so unselfishly proved them in the large things that call for sacrifice of estate and even of life itself.”

On top of this, Ball State was founded in the same year. The university today serves as the heart of Muncie’s economy, and back in 1918 classes had begun. It’s interesting that both of these events would happen at the same time, as the founding of BSU marked a big economic change in Muncie.

Protests Against Waelz Sustainable Products in 2019

One of the biggest recent controversies in Muncie was in 2019 when Waelz Sustainable Products wanted to build a new plant here. Residents were angry when they discovered the environmental impact this would have and effectively protested the matter.

Early in 2019, $75 million was invested for Waelz Sustainable Products to build a facility at the site that was formerly BorgWarner. The plan was for the plant to be operational by late 2020 with 90 jobs added over several years in two different phases. City Council approved the ordinance for the project on July 1st and the Indiana Economic Development Corporation offered $5 million in tax credits for WSP. While it appeared at first glance that this would bring back industry to Muncie with an environmentally friendly recycling plant, it would have been the highest emitter of mercury nationwide and the 15th highest emitter of lead. For workers at the plant and people in Muncie, inhaling this would cause long-term effects such as lung cancer, respiratory diseases, and cardiovascular disease among other things.

The of the early factors that built opposition was Seth Slabaughs article on July 20th, where he interviewed Bryan Preston, GIS technician from Muncie, as well as Alex Sagady, a retired environmental consultant from Michigan. Sagady: “This plant will generate considerable amounts of mercury emissions, clearly in the same ballpark with what they admit to be their mercury emissions down there in Alabama. But the primary health effect to worry about is exposure to PM10 (inhalable particles) and PM2.5 (fine inhalable particles) right next to the plant.” Preston was the first to contact Sagady who volunteered his time to turn the situation around. Their goal was to get the community onboard to stop the project because while the City Council had already approved the project at this point, the Indiana Department of Environmental Management still could be halted from approving the construction permit.

On August 5th at City Hall, more than a thousand people went in the auditorium, hundreds of them had to stand outside due to limited capacity, and they called for the IDEM to deny the facility a construction permit. Around this time a Change.org petition was made to call on City Council to pull the plug on the project, which received over 10,000 signatures by the time it closed. Throughout the month, a lot of the objection to the project came from neighborhood groups, churches, and civic groups. Avondale United Methodist Church pastor Josh Arthur led this charge through social media, events, and overall organizing and educating the community on the issue. One reason for the large community involvement in stopping the project was the already outrageous FBI investigation against mayor Dennis Tyler and others, because such controversy made our community skeptical of the project and unable to fall for the pitch from WSP, who even made the claim that there would be no emissions at all.

On August 20th, the City and Waelz pulled the plug on the project. When the project was stopped, Muncie Redevelopment Commissioner John Fallon said the City’s exit from the project was purely because of the citizen’s protest. The same day, Josh Arthur had organized an educational forum that took place hours after the announcement. When introducing speakers before an enthusiastic crowd, Arthur said: “Everybody rose up in unity, and I think this momentum does not matter what party you are a part of (applause) but that this momentum will carry on. I don’t think this is a flash in the pan, what we’ve learned is that we can form small groups all over the county that work on particular issues, share that information, and appropriately influence our decision makers. And maybe we thought we couldn’t do that before. Maybe we thought it wouldn’t matter, but we know differently now.”

The protest on August 5th was the largest for a long time in Muncie up until that point. To quote Bryan Preston, “the movement to shut down WSP’s proposal was a fundamentally broad-based grassroots movement. There were leaders in the movement, but there was no central organizing. There were many leaders and many, many people working independently to create the outcome we wanted.”

The Paving Trust Scandal of the Hampton Administration

Muncie has been a corrupt city for a very long time, and that was definitely the case when John C. Hampton served as mayor from 1926 to 1930. His term can be largely distinguished by the scandal coined as the “Paving Trust.”

It starts in 1926. Contractors Arthur K. Meeker and Albert N. Shuttleworth would submit low biddings for construction of streets, alleys, sidewalks, curbs and gutters. Though in the Hampton administration, the low bids submitted were all rejected. Instead, four private companies that were not low bidders were almost always picked instead and the justification for this by the Board of Public Works was that the proposed bidders weren’t reliable enough. A heavy burden was put on the property owners as they were forced to pay even more than normal for construction in their neighborhoods and it was later proven that hundreds of thousands in bribes were paid to members of the Hampton administration. The companies chosen(Muncie Construction, Hawkins and Beall, John E. Bell and Curtis and Gubbins) were substantially higher bids and the materials the companies bought were all from the Magic City Supply company, managed by the brother of B.W.A president Harry Hoffman.

Many citizens started attending B.P.W meetings and were furious. Already before the rejection of the low bids, the community was angry when a dirt cheap truck was bought by the B.P.W for $2,600.25 from coal company employee Oliver Williams. It was made without advertising for competitive bidding, it was an illegal purchase, and soon after the Municipal League of Delaware County started an investigation. The Evening Press and The Star for the most part didn’t touch what was going on, though leading the charge with the accusations was George R. Dale, editor of the Post-Democrat. After focusing his editorial efforts on courageously attacking the Klan throughout Indiana, Dale used all his time to attack how streets were being paved. Though later on, another editor Wilbur Sutton of the Evening Press would report on the scandal as well, when many unneeded improvements were being done in the city “where the benefits of the property owner involved, if any, have been out of all proportion to the cost” as Sutton wrote.

Dale was elected mayor in 1929 and campaigned on stopping the paving trust. Early on in his term he claimed to have made the “key master” admit guilt however Dale was limited as mayor due to constant legal battles and griping with council members. Despite so much concern from residents the scandal was never taken on by law enforcement.

Kennedy's Visit to Muncie

While campaigning for president, John F. Kennedy gave a speech to thousands of people in Muncie. It was one of our largest political rallies with lots of support from union members.

On October 5th, 1960, John F. Kennedy visited Muncie to give a speech at the County courthouse. His brief speech was received by 5,000 people as he spoke about his opponent Richard Nixon and statements he had recently made about Kennedy. “Nixon, speaking in Boston the other night, said I was another Truman, and I said he was another Dewey, and he is. (applause and laughter). Any candidate who considers our program extreme, any candidate who is opposed to $1.25 minimum wage, or medical care for the aged or a decent housing bill, any candidate whose party is only able to get our steel mills working 50 percent of capacity, who is only able after the recession in 1958 to have this economy drifting along – I think we need a change. (applause).”

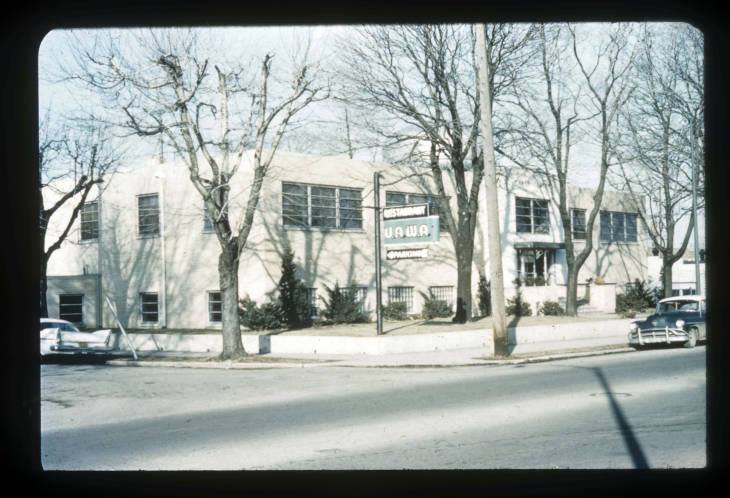

It’s really no surprise that his policies would receive droves of support from residents here. With so many manufacturing jobs, there existed massive support for unions which paved way for the United Auto Workers Union. Muncie’s UAW Local 287 was officially started on March 25th, 1937 with eighteen charter members and even support from Mayor Rollin H. Bunch, who allowed members to meet in the City Garage. Before the UAW was formed, union efforts in Muncie were looking grim. Both the Evening Press and The Star often wrote against their attempts to unionize in the city because they as well as leaders in the community wanted to keep these efforts out of Muncie. But the union grew, and over the years became so popular that Paul Cooley, who was an active member and served as president of UAW for a year, was later elected mayor for two terms. The Star reported the day after Kennedy’s speech “About 500 workers at Warner Gear plant 3, most of them members of Local 287, United Auto Workers, left their jobs for about an hour and half in a spontaneous demonstration for Kennedy. They walked away from their machines about 10:30 and the belated motorcade did not arrive until about 11:50. The Warner Gear employees blocked three of the four lanes of Ind. 32 as Kennedy approached and the Democratic nominee stopped for a four-minute talk.”

Kennedy stopped to meet mayor Arthur Tuhey, city attorney Marshall Hanley, Indiana governor Matt Welsh and many others. It was a memorable moment for Muncie as well as a proud moment for his supporters.

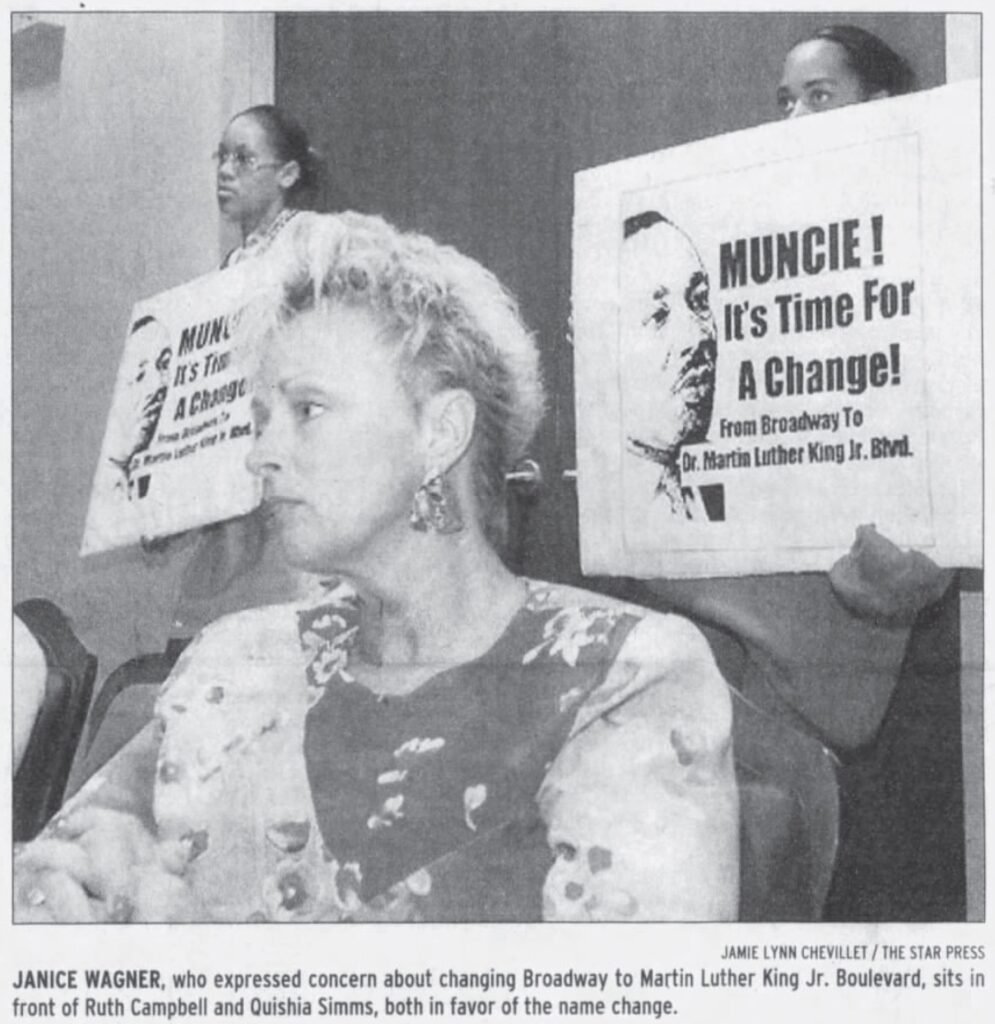

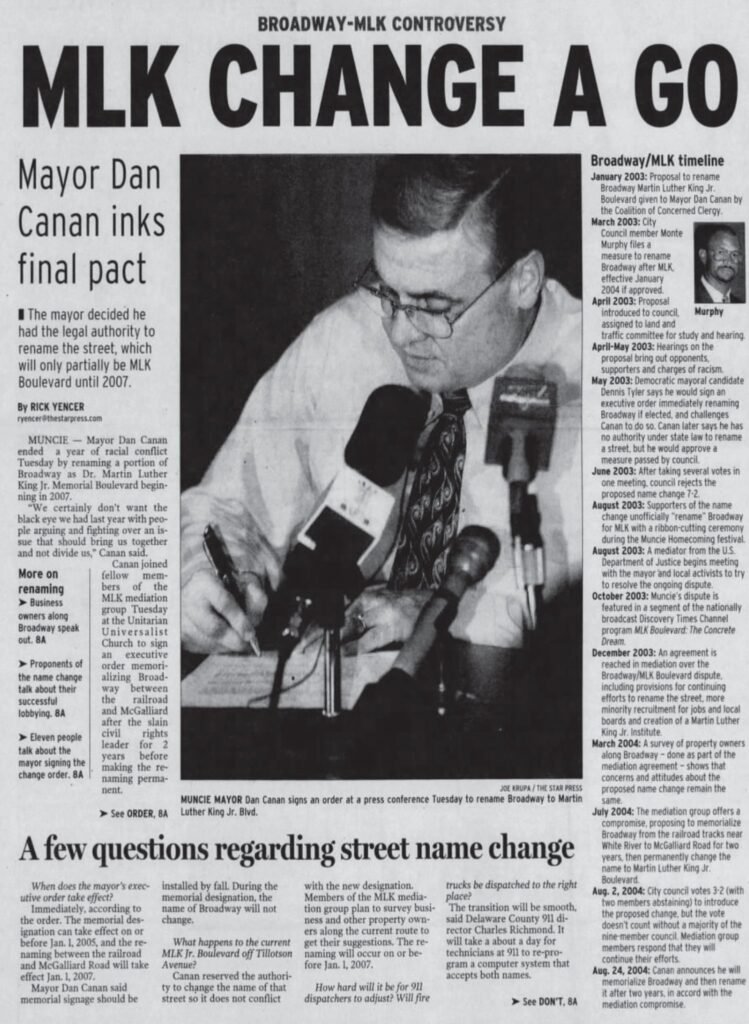

The MLK Boulevard Controversy 2003

The MLK Boulevard controversy was an event in Muncie between 2003 and 2004 that demonstrated how much change was needed in the community for minorities.

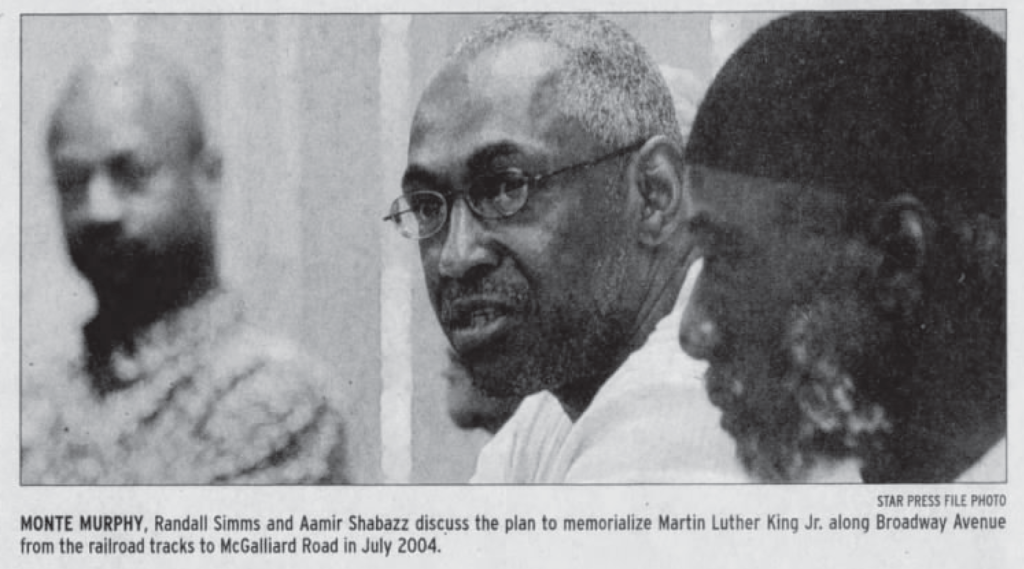

Early in 2003, a proposal was made to rename Broadway Street to Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard by the Coalition of Concerned Clergy, a group of Black ministers who created a petition signed by several thousand individuals to change the name. In March, City Council member Monte Murphy filed a measure for the renaming to happen in 2004. Additionally, supporters added demands as time went on such as better policies for minority recruitment for municipal jobs, creating a Public Safety Community Relations Board, a Neighborhood and Economic Development Corporation, and a five-member committee for the founding of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Institute. Many residents who were against renaming the street claimed their concern had to do with changing their addresses (which wouldn’t take place immediately as residents would receive at least a six-month notice) as well as worry that businesses located on the street would lose money from changing letterheads and business cards. Several meetings took place and one in particular held on May 27th included lots of heated exchanges. The event escalated even further when a county employee called students holding signs the N-word, attendants of the meeting were appalled. On another occasion on May 30th, the street sign marking MLK Jr. Boulevard was defaced.

The day after the meeting on May 28th, Dennis Tyler, who was running against Daniel Canan for mayor at this time, confronted Canan to change the street name, saying “it is time for Mayor Canan to step forward and show some leadership.” Canan denied he could do it unless a measure was passed by council, however Monte Murphy brought up how Anderson’s mayor was able to rename Pendleton Avenue to MLK Jr. Boulevard with an executive order. The council rejected it in June with a vote of 7-2. The issue went on longer until August 24th, 2004, when Canan finally decided to change the street name. Canan stated “We certainly don’t want the black eye we had last year with people arguing and fighting over an issue that should bring us together and not divide us.” The change was planned to occur at the start of 2007, and the executive order was signed at the Unitarian Universalist Church.

The whole year of debating the issue showed that much progress was needed in terms of race relations for Muncie. Most of the requests that supporters asked for were never done and one business, Ed’s Warehouse, decided to close despite doing well financially. Muncie was featured in the 2003 documentary “MLK Blvd: The Concrete Dream” which featured people in our community during the shambles.

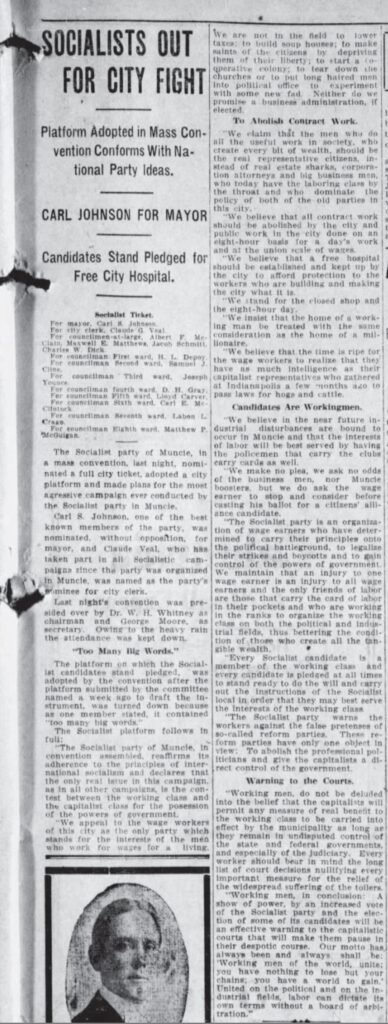

The 1913 Mayoral Election

One of our most hectic mayoral elections was in 1913, in which Rollin H. Bunch was elected for his first term. Five different parties had a candidate for mayor, and each of which had a fair chance of winning.

The Star wrote that year in October: “The municipal campaign that is being waged in the city of Muncie is, in many respects, the most remarkable that has ever been known by the citizenship of the Magic City…” and undeniably it was. The election of 1913 had not only a third party candidate, but five in total. Other than the Democrat and Republican candidates, there was a candidate on the Progressive party, the Citizens party, and the Socialist party. Though Bunch would win the election by a big margin, none of the five parties could be entirely dismissed from winning, in fact the Progressive and Citizens candidates each received more votes than Republican nominee Michael Broderick.

Even though these three additional candidates and their supporters were against the two-party system, they were very opposed to each other. On one end was the Citizens Party which railed against corruption, advocated for clean government, regarded itself as bipartisan and even received support from the Evening Press. Candidate George Wilson, the Evening Press and Citizens party members were against the Progressives, who they deemed as being part of a tri-partisan machine with the Democrats and Republicans. In return to their party getting support from the Evening Press, the Progressive party had support from The Star. Candidate Harry Kitselman, who later became president of the Muncie Chamber of Commerce and even made a run for Congress, ran as a Progressive in 1913 and according to Thomas Buchanan “favored a female police officer, more municipal playgrounds and parks, a city market, and a new city hospital.” And lastly, the Socialist Party “warns the workers against the false pretenses of so-called reform parties. These reform parties have only one object in view: To abolish the professional politicians and give the capitalists a direct control of the government.” Their candidate was Carl Johnson, a pharmacist and travelling salesman, who advocated for a free hospital run by the city, working men to get the same equal treatment as millionaires, and for public work in the city done on an eight-hour basis.

As a result, Democrat Rollin H. Bunch received 2,254 votes, Progressive candidate Harry Kitselman had 1,367, Citizens candidate George Wilson had 964, Republican Michael Broderick had 812 and Socialist Carl Johnson had 599. It was a time throughout the country of political fragmentation and Muncie was no exception.

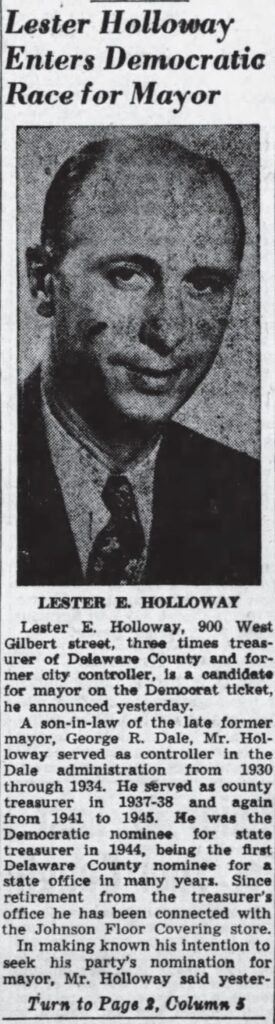

The 1947 Democratic Primary

The mayoral primary election of 1947 was a big year for factionalism in the Democratic party. Lester Holloway faced two big challengers yet won by 475 votes.

Unsurprisingly, one candidate in the race was Rollin H. Bunch, who served as mayor three times and consistently ran in every election from 1933 and onwards until the end of his life. Holloway, who also previously served as City Controller and three terms as County Treasurer, was encouraged to run by Democratic party chairman Oscar Shively. Shively, however, would then announce his own candidacy for mayor. Shively believed that he could beat Bunch only if another well respected candidate were to get in the race to split the vote, thus helping himself win. These three individuals would be the major candidates with years of experience under each of their belts. Additionally, C. Barney Minch and Carl T. Bartlett also entered the race with very little support.

Bunch was a political boss in his era and was first elected at the age of 32 in 1913. He was notorious for committing mail fraud in his second term as mayor, though he planned on winning this election through his decades of support from those he appointed and loyal southside residents. Shively expected support from precinct committeemen and campaigned to cut expenses, bringing in qualified appointees, and overall aiming for future growth in Muncie. For Holloway, it was not only the reputation he had from working in George Dale’s administration but also his aim to get crossover votes from Republicans, something very profound for a Democrat to do in a primary election. He drew support also because of his business experience and knowledge of city finance. At the time when all three announced their candidacy there was no obvious winner, each of the three had their own different appeal and were each well supported. Charles White wrote in the Evening Press “no unbiased observer as late as Saturday would venture a prediction as between Dr. Bunch. Mr. Shively and Lester Holloway.”

The results were a surprise for Bunch, who previously won every Democratic primary he ran for in his life. Shively wasn’t successful in his attempt to neutralize his two opponents and was behind both of them in votes. Holloway successfully won the race with 2,554 votes, Bunch got 2,079, Shively with 1,813, Bartlett with 347 and Minch with 59. Holloway also later won the general election and was inaugurated as mayor in 1948.

A Brief History of Tuhey Park

With the proposed YMCA building at Tuhey park becoming a hot topic in recent months, the sustantial history of the park has also been brought up too.

Tuhey Park came out of the depression era in our country, thanks to the Public Works Administration in 1933. Edward Tuhey, whom the park is named after, died in the same year. He served two terms as mayor, one between 1899 to 1902 and another between 1910 to 1914, then ran for a third term only to lose in the primary to Rollin C. Bunch. Tuhey passed away in 1933 and that year Northside Park was effectively renamed Tuhey Park. Mayor at the time George Dale, also editor of the Post-Democrat, wrote an obituary and had this to say about Tuhey and the new park:

“As mayor of the city of Muncie for two terms it was during his last administration that the public park system now so thoroughly enjoyed by all citizens was inaugurated. Both McCulloch and Heekin parks were acquired during that time and the present day park system is built around these two beautiful sites. In tribute to this activity of Edward Tuhey, Mayor Dale has proclaimed the naming of Muncie’s latest park between the High and Washington street bridges as ‘Tuhey Park.’”

Years later in 1956, a time of racial segregation, Roy C. Buley led several Black residents to swim at Tuhey. Buley believed the pool should be open to all races, he said in The Star “there are some who never went there because they believed it to be an exclusive pool.” The event caused an uproar in the city, and as a response the pool was closed by city police that day. Mayor at the time Arthur H. Tuhey, son of Edward Tuhey, ordered the pool reopened and desegregated all city pools.

Chris Flook recently wrote about Tuhey park in the Star Press. Click here to check it out:

Carey vs. Wilson

Muncie’s mayoral election of 1979 got the attention of filmmaker Peter Davis and became a subject for his 1982 miniseries “Middletown.”

The Middletown documentary series consisted of six episodes that explored work, play, family, religion, education, and politics in Muncie. They aired on PBS in 1982, with the exception of the last episode, and were filmed for three years by creator Peter Davis. Davis, who was especially known for his Vietnam War documentary “Hearts and Minds,” set out to show the changing values of our community. Along with him was a crew consisting of other documentarians and even Ball State faculty. One of the directors was Tom Cohen who did “The Campaign,” an episode focused on the mayoral election of 1979.

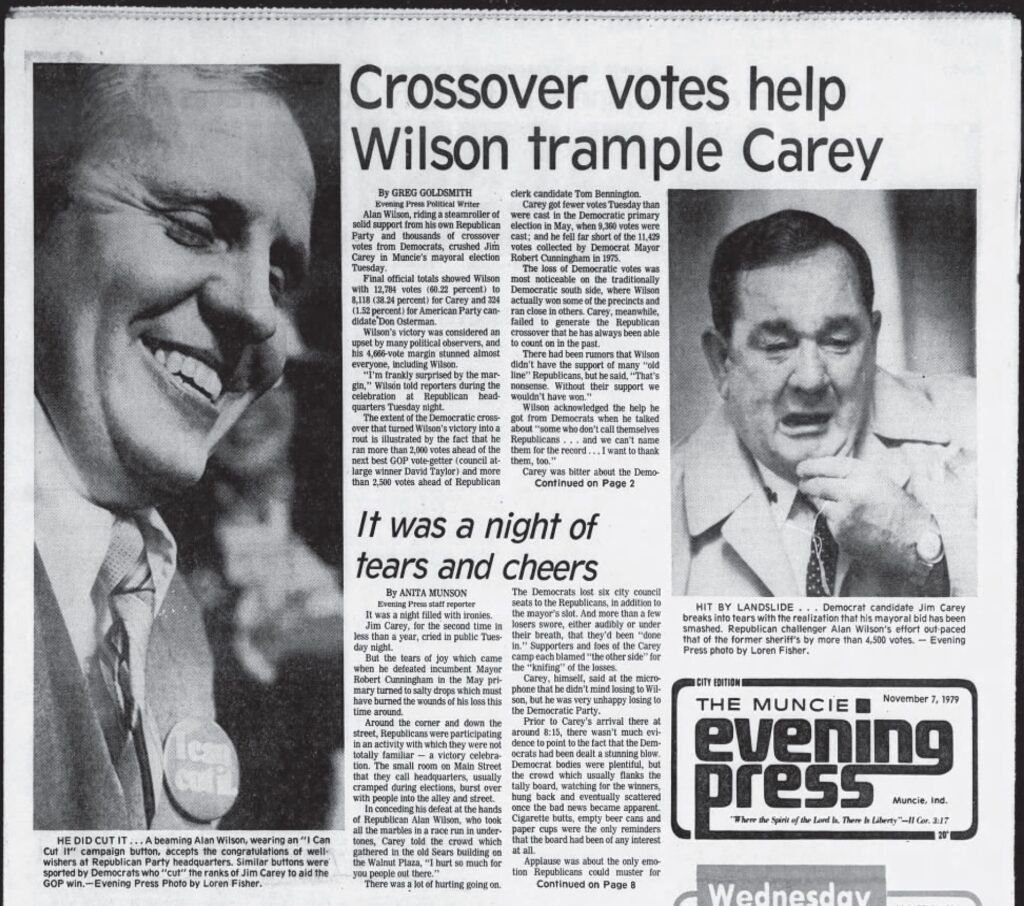

The 77 minute documentary focuses mainly on James P. Carey, the Democratic party nominee who lost to Wilson by 4,666 votes. WBST commentator Greg Goldsmith said that the election would come down to Carey’s appeal. “Jim Carey is the issue of the election, don’t ever forget that. You either vote for Jim Carey or against Jim Carey for the most part in this election. That’s the way it goes down. Of course, you’ve got your hardcore Republicans voting for Alan Wilson, but what’s going to make the difference is whether they vote for Jim Carey or vote against Jim Carey, not whether they vote for Alan Wilson.” He goes on to say that there are many Democrats crossing over because of Carey’s prior corruption charges, the other commentators agreed and one suggested 75% of the vote is for or against Carey.

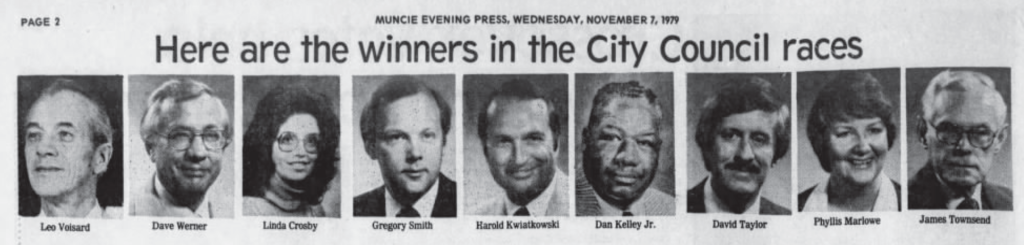

The Evening Press even reported in their headline that there were thousands of crossover votes going to Wilson. It was a big deal considering Democrat mayors achieved solid victories in all their elections since 1967. Alan Wilson became the first Republican mayor since John V. Hampton.