What Would it Take for the Democratic Party to Change?

7.27.2025 / Essay / Daisy Dale

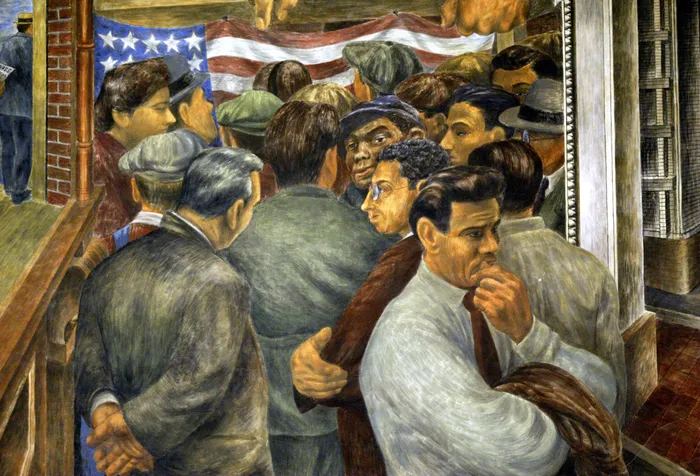

Portion of Ben Shahn’s mural from the Roosevelt Public School.

To make my views clear I will start out with this statement: I believe American conservatism fundamentally can’t do anything good for labor. Deregulation and privatization not only allow monopolies to crush your chances to organize at your job, but historically have allowed shocking threats to the livelihoods of labor organizers. But, there haven’t been any considerable attempts made recently by the Democratic party to draw in support from that end, especially compared to the New Deal era.

Progressives last year were angry when Teamsters President Sean O’Brien made an appearance at the Republican National Convention. It was seen as a soft endorsement by the Teamsters for Trump, however O’Brien was actually open to also speaking at the DNC and was denied that opportunity. It’s also worth mentioning that his new podcast features many left-wing guests, so it’s not as if he’s not willing to work with leftists and the Democratic Party. Is that a sign of “realignment” of party affiliation for labor? Certainly not. Because the Republican party in its current shape will still continue to make it harder for unions to have agency for collective bargaining, and beyond that are already making life unlivable just with recent legislation. It’s rather a process of dealignment, which I’ll detail more about later, that’s the most accurate way to describe the ongoing phenomenon. And the only way the Democratic Party can win elections is if we reverse course on this.

Back in November I wrote two post-mortem articles after the election. One of which was titled “From Creating A Bogeyman to Digging Your Grave“, a piece focusing on the biggest issue that was ignored by most pundits: the departure of New Deal liberalism and how that was cemented by the presidency of Bill Clinton. While Morning Joe was quick to blame the 2024 loss on an overemphasis of social issues (transgender issues uniquely), more and more of the party base has started to see their leaders as feckless and unable to push through on an enticing economic platform.

That critique is nothing new, and writer Thomas Frank has used multiple books to articulate the same messaging. But I was surprised when more attention was recently brought to Post-Democrat founder and my great-great-grandfather George R. Dale. Most of the recent conversation surrounding his fight with the KKK in Muncie, by journalist Dan Sinker as well as the Too Many Tabs podcast, has centered on how the Left and the Democratic party today should fight against authoritarianism. Muncie in the 1920s was the town where the constitution didn’t apply, and Dale was far from the spineless party leaders who would rather lay low than work to stop the Republican agenda.

That same decade witnessed a broader turn for the Democratic party nationwide. The party lost three elections in a row (1920, 1924 and 1928) but followed with one of the most popular presidents of all time, Franklin Roosevelt. While the political factions in the party were each a mixed assortment on policy, there was a semblance of left-wing versus conservative forces battling it out as the decade went on.

Party Politics in the 1920s

In a nutshell, the whole party had a major evolution between the presidency’s of Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt. If Wilsonian Progressives, as Historian Gary Gerstle characterized it, emphasized “character building,” “Americanization,” “social hygiene” and “clean government,” Democrats in the ’30s emphasized “security,” “opportunity,” and “industrial democracy” by comparison.1 And between the factions at play, it was increasingly becoming rugged individualism versus collectivism. Many leaders and supporters believed that they should seek the same type of business friendly candidates as the Republicans, but this had pushback within the party every election. As one politician wrote, “we cannot win by letting folks think that the Republican Party is 51% bad and we are only 49% bad.”2

While there were limits to Roosevelt’s New Deal, through capitulations to Southern Democrats, it did not implement racial discrimination by design as has been repeated. (See Katie Rader’s article “Race and The New Deal” for more info).5 The bigger take away from this point is that if we are to make a better counternarrative to the Right, we should be able to point at the success from this time period. That includes the 1935 Wagner Act ensuring the right to unionize (ended in 1948), the very inception of Social Security, or even the potential for the Second Bill of Rights that was proposed by Roosevelt.

Democrats Today

Long after the presidency of FDR, New Deal liberalism acted as a long running economic order until the rise of Neoliberalism in the 1970s. A new consensus was created by both parties, whether under the leadership of Reagan or Clinton, that ensured deregulation and privatization would go through the roof in the United States. After decades of this, the Recession of 2008 seemed set as a perfect time for a new political transformation, much like the 1920s, to manifest. So was the COVID-19 pandemic, too, and in both years Democrats were elected to the presidency.

The best explanation of what’s put such change to a halt is that we now have a party constantly wanting to play it safe with the current political climate. As elections become increasingly more expensive, political consultants have a larger role in the party and the candidates, more interested in repeating any semblance of past success rather than advocating for universalist programs. Rhetoric from the party today gives vague notions of economic radicalism, but no delivery. And yes, there is a large part of the electorate that’s harder to appeal to, but appealing to the center is an oversimplified diagnosis of the problem.

We need to consider that many voters that are considered to be “long gone” can actually be appealed to with economic populism. And while social issues are more complicated here, it’s not to say we have to acquiesce on support for marginalized groups, for instance. In general, there are very few hardline ideologues when it comes to policy, and so what needs to be tapped into is a sense of power in who we’re voting for. That can be done if the policy happens to be universalist programs, or protection of labor unions, or putting up a real fight against the rich.

In Jared Abbott’s essay “Understanding Class Dealignment”, he favors the idea of the Democratic Party realigning itself back to working-class voters and without entertaining the idea of a third party. He also points at the success of the 2022 midterms where candidates who used populist rhetoric, speaking in favor of a jobs guarantee and increasing the minimum wage, ran more successful campaigns. Abbott identifies five ways to reverse the course of dealignment:

1. To make more effective working-class appeals, candidates should run on bold anti–economic elite platforms.

2. To make more effective working-class appeals, candidates should run on economic policies that people care about and should try to raise the salience of economic issues on the campaign trail.

3. To make more effective working-class appeals, candidates should run more working-class candidates.

4. In the medium term, Democrats and progressives will

have to find ways to re-embed unions in working-class

communities.

5. Ultimately, however, a major working-class realignment toward the left will only occur if progressives deliver major, epoch-defining legislation that creates broad new working-class constituencies on a scale approaching the impact of the New Deal.

Since 2016 there has largely been a dismissal of the idea to appeal with economic populism, with pundits saying that it always leads to demagoguery. But with the political consultants, academics, and professional class leading the party for decades at this point, that isn’t a risk we can be taking anymore. The faux-populism seen on the Right doesn’t have a clear future for most of the population, and combating it with a platform of real conviction, anti-establishment politics, and championing the working class is the only way out. If we really believe the only opportunities lie in the next few elections, we can’t keep appealing to non-existent centrist voters and ignore the popularity of this platform.

Daisy Dale

Notes:

1. Gerstle, Gary. “The Protean Character of American Liberalism.” The American Historical Review 99, no. 4 (1994): 1043–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/2168769. p. 1044; this characterization is also what Historian Richard Hofstadter used long before.

2. Craig, Douglas B. “After Wilson: The Struggle For The Democratic Party, 1920-1934.” University of North Carolina Press. 1992. p. 212; Quote is from Josephus Daniels.

3. ibid p. 176.

4. ibid p. 55.

5. Also available for free here: https://jacobin.com/2024/09/new-deal-racism-welfare-labor/. See also: Reed, Adolph. The New Deal Wasn’t Intrinsically Racist.” The New Republic. 2019. https://newrepublic.com/article/155704/new-deal-wasnt-intrinsically-racist.