My Hometown Is More Than a Case Study

6.12.2025 / Op-Ed / Daisy Dale

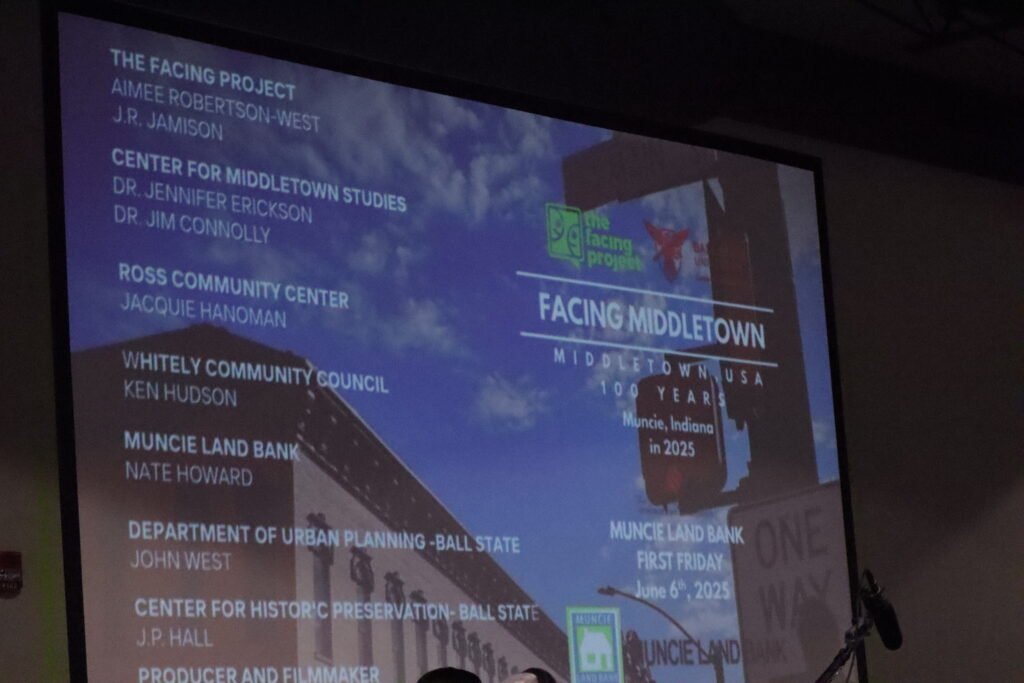

Last Friday, a launch was held for an upcoming book and documentary on Muncie. Of course, if you’re familiar with our reputation as the typical American town, it won’t surprise you to hear that the project is titled “‘Facing Middletown – 100 Years Muncie, Indiana in 2025”. In it’s current stage, a group of Middletown researchers, filmmakers and others will be facilitating discussions, interviewing locals, and salvaging their daily lives through videos and writings.

Regardless of whether you see Muncie as the most average city in America, it admittedly would be great to see how we underwent events like deindustrialization or the COVID-19 pandemic. And since I recently wrote a book about Muncie in the 1910s, the Middletown studies were a benefit to me. But part of me can’t stand seeing us be reduced down to that study, to the point where I made zero mention of the Middletown studies in the book (outsides of notes at the tail end), and only gave faint mention of the authors who wrote it. Maybe it’s the same way I feel when Muncie is only thought of as the place of Garfield or David Letterman or the Ball Family, but above all I just have a hard time seeing us a standard city.

To me, Muncie’s an eccentric labor town at heart. That might not be how people doing real estate deals in our town see it, or it might be a step off from how my civically-involved friends even do, but I’ve decidedly held onto that view. From conversations I’ve had with the people running this new part of the studies, they’re aware that it needs to be done right and to not just show academics and business people talking about their experiences. They’ve explicitly pointed out that academics have made the mistake of treating residents like lab rats, or the exclusion of Muncie’s Black community from the original study. But did the original study by the Lynd’s even reveal Muncie as the most average city? Likely not, but the significance of it has more to do with what it’s meant over the past century than the Lynd’s exactly “hitting the dot” with the original books.

Just a few thoughts: first of all, Muncie being chosen in the study was a lucky accident. Earlier on in its development South Bend was being considered, as well as Jackson, Michigan, Rockford, Illinois, Steubenville, Ohio and Kenosha, Wisconsin.1 Ironically, John D. Rockefeller had a big role in funding what was originally called the “Small City Study.” While Robert Lynd despised Rockefeller, even writing scandalous articles on that blue-blooded Oil Baron, Rockefeller managed to have an influence on how the study portrayed economic class and religion.

Secondly, while the Ku Klux Klan had a massive domination over the city, they did very little to capture it. There are some pretty revealing interview notes that can be found in their personal papers, but despite how big of a deal the Invisible Empire was in Muncie it wasn’t talked about nearly enough. When it came to the Black community, who were segregated in parks thanks to the Klan, they were largely ignored in the books because the Lynd’s were more interested in the perspective of native-born Protestants. And so years later when The Other Side of Middletown was published, the 2001 book tried to address that omission by compiling essays from Black community leaders and including what was excluded about the 1920s.

As an alternative, for a better sense of our community and what to make of it, we should look at how some of our local historians and activists shaped Muncie’s identity. Hurley Goodall (1927-2021) was a politician who saw value not only in serving in the Indiana General Assembly, but through salvaging the history of our hometown. His contributions range from research on Fredrick Douglass’s 1880 visit here to being the driving force behind The Other Side of Middletown, and that’s on top of writing other books and donating most of his writings to Bracken library. Bob Cunningham (1928 to 2005) prioritized historic preservation, whether as mayor in the late ’70s or as Center Township Assessor. He painstakingly compiled all city election results into one book and as a cartoonist made the Growing Up in Middletown series, and like Goodall donated his research to Bracken (some materials even date back to the 1890s).

I can’t pretend I have the most clear idea of what our community today embodies. We’re more fragmented than ever before and we have less and less spaces to interact with each other, so it makes it nearly impossible to decipher that. Putting Muncie in the spotlight again has a lot of good potential for us, but there’s no reason to believe that our fame should start and end there. Right now, the project is open to finding residents to tell their stories, and we have an opportunity for this not to have the same faults from before.

Notes:

1. Fox, Richard W. “Epitaph for Middletown,” in The Culture of Consumption: Critical Essays in American History, 1880-1980. ed. Richard Fox (Pantheon Books, 1983), pp. 113, 119.