The Municipal Reform of Harvey Milk

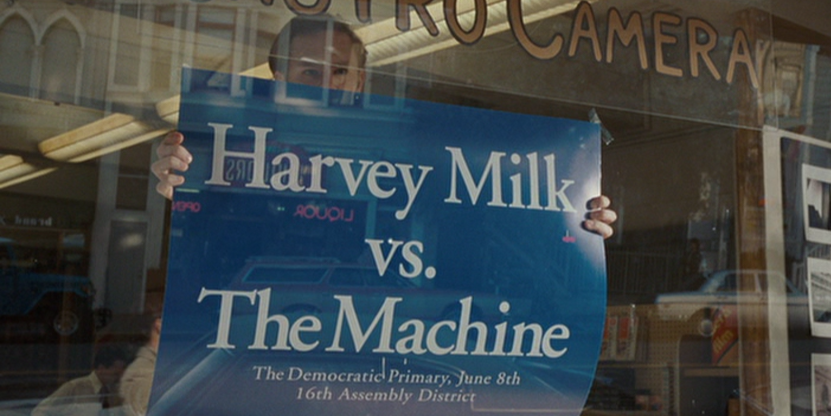

From “Milk” Dir. Gus Van Sant, 2008

Harvey Milk’s work in San Francisco was short-lived due to the assassination of him and Mayor George Moscone. He served on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors (a position equivalent to a city council-member in other cities) but he only served that role for 11-months. His major accomplishments on a state and national level included his campaign against the Briggs Initiative, a proposition that would have made it illegal for gays to be teachers in California, and his public opposition to Anita Bryant, a singer best known for several orange juice commercials and her outspoken homophobic stances.

This isn’t to say that his activism has been mythologized, or that his image has been flattened, but the originality in what he was doing in San Francisco has been greatly overlooked. As we’re thinking now more than ever about where we can find institutional leverage, given how bleak the news continues to be, Milk holds up as a politician who drew more interest in local politics by his nearby City Hall than for the sort of politics that begin and end in Washington.

San Francisco had become a mecca for the gay community. The Castro area in particular evolved in the ’60s and ’70s to become a region for the hippie movement and sexual revolution that the time period was known for. Milk moved there with his partner Scott Smith in 1972, as tens of thousands of gays and lesbians were doing the same in that decade.

He started running his own campaigns in 1973, running three times unsuccessfully before his first victory in 1977. When George Moscone was elected mayor in 1975, he appointed Milk for the Board of Permit Appeals, and continued a diverse set of appointments for the rest of his tenure. However, this didn’t stop Milk from running for State Assembly that year. Not only did he risk another failure, which did in fact happen to him in that election, but in early ’76 Moscone removed him from the Board of Permit Appeals, because of his rule not to allow appointees to run for office. Democratic leadership had also already picked a candidate, Art Agnos, to run for Assembly.1

In his successful ’77 campaign for Supervisor, he gained a major advantage when it was decided that voting districts would be established instead of only city-wide races being held. District 5 that he ran for was conveniently the Castro District, where his camera shop was located and had the highest concentration of San Francisco’s gay population. Milk would receive 1,450 more votes than his most popular opponent,2 and in spite of Moscone reportedly supporting another candidate Rick Stokes.3 Milk was willing to work with everyone when he started, including conservative-Democrat Dan White, although his win for Supervisor wasn’t without it’s unique party infighting.

Milk speaking at Union Square rally on the night of Anita Bryant’s victory in Miami. By Jerry Pritikin.

Pin of Diane Feinstein as a Circus Clown. From Personal Collection of Daisy Dale.

“On the local level, you’re finding that the battle against Briggs in this city is putting a lot of gay people into the political process — people who have never been in it before. There will be a carry-over that will affect all political races in The City. Once people become more politicized many of them stay politicized. That means there will be more gay people involved — not only in running for office, but also involved in initiative campaigns, proposition campaigns and working for candidates. I guess the best way of putting it is, you’re going to see the maturing of the gay political consciousness because of the Briggs initiative.”5

His Leverage and the Boycott

As a result, five of the six distributors signed the contract, and gay truckers were hired with Falstalf, Lucky Lager, and Budweiser.9 Later on, the local Teamsters endorsed Milk in his 1977 campaign.10 Now after his first successful campaign, Milk would be inaugurated on January 9th, 1978.

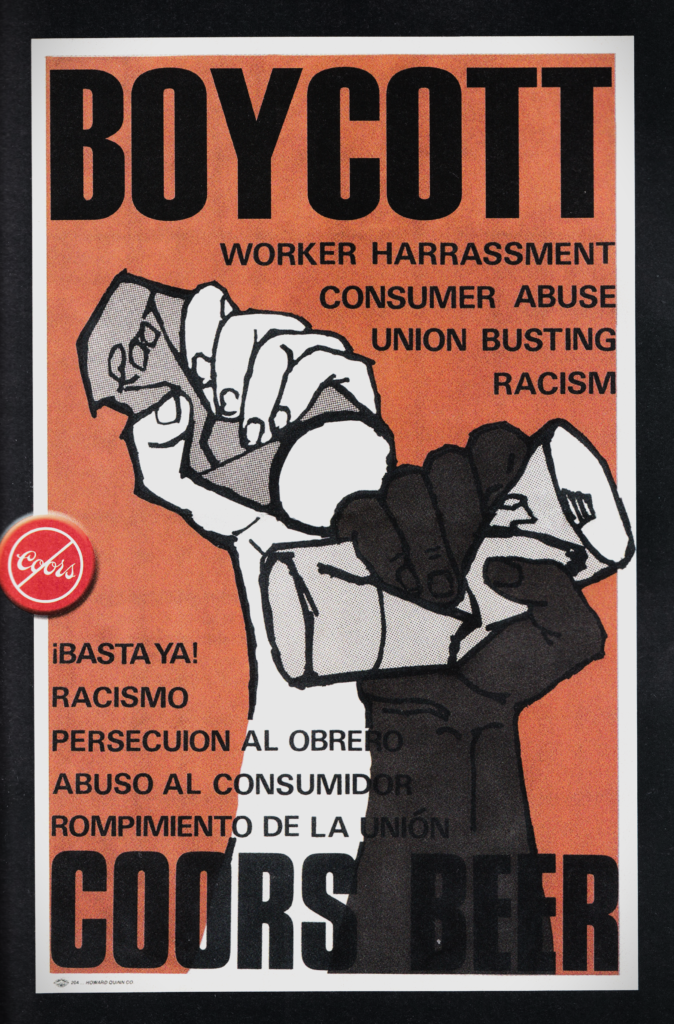

Coors Boycott poster and button re-created for the movie Milk.

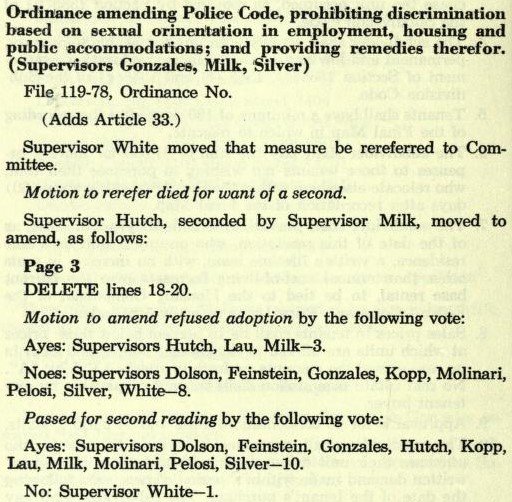

Board of Supervisor Accomplishments

“The media coup of the year and the issue that best symbolized Harvey’s theories on how government should work, centered on the mundane subject of dog feces. Survey after survey showed that sidewalk dog droppings were San Franciscans’ biggest complaint about city life. Milk, therefore, sponsored a bill requiring dog owners to clean up after their pets, waxing philosophically that, ‘It’s symbolic of all the problems of irresponsibility we face in big, depersonalized, alienating urban societies.’ […] ‘Whoever can solve the dogshit problem can be elected mayor of San Francisco, even President of the United States.’ Years later, some would claim Harvey was a socialist or various other sorts of ideologues, but, in reality, Harvey’s political philosophy was never more complicated than the issue of dogshit; government should solve people’s basic problems.”18

What Could Have Been For Housing

His anti-speculation tax, or “Real Property Tax” ordinance that would have put a higher levy on properties being quickly flipped by real estate moguls, was an unrealized idea. It only applied to homes with three or more units, and over the course of six years would steadily decrease. San Francisco in the late ’70s was having its own surge in housing prices that was nothing unlike the gentrification spoken about in the city today.

Talks started in May of 1978. The cause brought together a long list of groups endorsing the ordinance. The biggest advocate group was the San Francisco Housing Coalition. The San Francisco Examiner reported: “citing more than 70 such examples of fast turnover and hefty profits and some 30 examples of sizable rent increases without corresponding improvements in the properties, the San Francisco Housing Coalition has begun beating the drums for a stern new anti-speculation law.20

"Our Street!"

Members of the Board of Supervisors noticed erratic behavior from Dan White before he killed Moscone and Milk. White had many personal issues with Milk, believing that he was involved in preventing him from being reinstated.25 But the “Twinkie Defense” he used to get a lighter sentence was unjustifiable. Instead of first-degree murder, he would be charged with two counts of manslaughter.26 The verdict of Dan White in May of 1979 continued sending shockwaves to San Francisco’s gay community. White would only be sentenced to five years in prison, putting Milk’s closest friends into distraught. This followed with the White Night Riots on May 21st that year, the biggest protest in LGBTQ history since the Stonewall Riots. It was indicative of upheaval not only in the U.S. but on a global scale. As Aaron Leonard described the various events of the late ’70s in Meltdown Expected:

“While the horror in Jonestown and the murders of George Moscone and Harvey Milk in San Francisco City Hall may have registered at the time mainly for their shock value, they nonetheless concentrated contradictions that were sharpening as the seventies drew to a close. And they came amid a shifting geopolitical framework–the unprecedented upheaval in Iran, instability in Afghanistan, and tectonic changes in China.”27

Daisy Dale

Notes:

1. Aretha, David. “No Compromise: The Story of Harvey Milk.” Morgan Reynolds Pub. 2010. p. 56.

2. “The Vote for Supervisor.” San Francisco Examiner. November 9th, 1978. p. 3. https://www.newspapers.com/image/460869863/.

3. Aretha, p. 66.

4. Shilts, Randy. “The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of Harvey Milk.” St. Martin’s Press. 1988. p. 198; Roberts, Jerry. “Dianne Feinstein: Never Let Them See You Cry.” HarperCollins Publishers. 1994. p. 153; Roberts, Jerry. “No Matter How Straitlaced She Seemed, Dianne Feinstein ‘Didn’t Care Who You Sleep With.'” Politico.com. September 29th, 2023. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2023/09/29/dianne-feinstein-legacy-00116902; I’ve used this last article for another article and based on memory there seemed to be some editing done to it over time.

5. Milk, Harvey. “The Harvey Milk Interviews: In His Own Words.” Vince Emery Productions. 2012. pp. 308-309.

6. Black, Dustin. “Milk: A Pictorial History of Harvey Milk.” Newmarket Press. 2009. p. 42.

7. Shilts, p. 83.

8. Blake, Kieran. “‘A Political Fight Over Beer’: The 1977 Coors Beer Boycott, and the Relationship Between Labour–Gay Alliances and LGBT Social Mobility.” Midlands Historical Review, Vol. 4 (2020). https://www.midlandshistoricalreview.com/a-political-fight-over-beer-the-1977-coors-beer-boycott-and-the-relationship-between-labour-gay-alliances-and-lgbt-social-mobility/.

9. Shilts, p. 84.

10. ibid, p. 98.

11. Roberts, p. 153.

12. Shilts, p. 199.

13. “Journal of Proceedings, Board of Supervisors, City and County of San Francisco.” Volume 73. 1978. p. 306. https://archive.org/details/journaljanjuneofproceed73sanfrich/page/306/.

14. Roberts, p. 154; Shilts, pp. 197-198.

15. “A Prop. 13 scare at the library.” San Francisco Examiner. May 9th, 1978. p. 6. https://www.newspapers.com/image/460982581/.

16. Shilts, p. 195.

17. ibid, p. 195.

18. ibid, p. 203.

19. ibid, p. 227.

20. “New anti-speculation law sought. War on profit in property sales.” San Francisco Examiner. May 9th, 1978. p. 4. https://sfexaminer.newspapers.com/image/460982437/.

21. Shilts, p. 194.

22. San Francisco Board of Supervisors. “File No. 120-78-1.” Personal Collection. 1978. Received October 24th, 2024. p. 37.

23. Leonard, Aaron. “Meltdown Expected: Crisis, Disorder, and Upheaval at the End of the 1970s.” Rutgers University Press. 2024. pp. 11-12.

24. Aretha, p. 58.

25. Leonard, p.11.

26. ibid, p. 129.

27. ibid, p. 154

28. Of the three tapes that Milk recorded his will on, the third missing one included this quote.

Other Sources:

Dreier, Peter. “Why Is Harvey Milk Still Dangerous, 46 Years After He Was Assassinated?” Jacobin.com. June 11th, 2023. https://jacobin.com/2023/06/harvey-milk-lgbtq-history-temecula-california-school-board-curriculum.

Katzman, Nat. “Moscone: A Legacy of Change.” PBS.org. 2018. https://www.pbs.org/video/moscone-a-legacy-of-change-hlozkc/.