Sept 25th, 2024 / Essay / By Daisy Dale

Between the ’20s and ’30s, Post-Democrat editor George Dale not only defined our local political scene, but dodged the Republican dominated legal system around him

The 1929 election in Muncie, as for many more local elections across Indiana that year, was a repudiation of what the Ku Klux Klan had done to the Hoosier community. If the fall of the Invisible Empire was obvious by the midst of the decade, then what followed was an embarrassing and tragic reminder. Membership lists, at least those that weren’t destroyed, were continually published for years after the fact. Klansmember Judge Clarence Dearth was impeached for his limits to free press, and the ongoing legal troubles he threw at George R. Dale, the great-great-grandfather of yours truly, were putting Indiana in the national spotlight.

When asked about George’s motivation, his oldest son Bud said that he simply hated hypocrisy. And that was the explanation I’ve decidedly held onto. Yet his youngest son Jack stated at one point that money was the driving force originally, and it wasn’t until his livelihood was threatened that it became rare for him to back down. Even with my surviving family members who were just a couple generations closer to the story, this still isn’t easy to decipher.

Timothy Egan’s recent book A Fever In The Heartland mentions the spectacle played out by George in Muncie, and it’s maybe one of a few times since the passing of George where interest for his story has peaked. Egan’s book reads like a balancing act between narrative non-fiction and investigating historical nuances, even addressing the historiography of the Indiana Klan in a way that’s accessible to readers. Though for the mentions of George and the Post-Democrat, that story has been somewhat flattened.

George and his views were sometimes idiosyncratic, erratic, and even contrarian to a degree. Though what best made him a left-leaning editor is that he rode the tide of transformation for the Democratic party, first by going against the machine politics perpetrated by local leaders, and second by publishing pro-labor stories at a time when the Democratic party was changing from a corporate party to a working class one. And his eventual term as mayor was ending just as the New Deal was kicking into gear. Even more puzzling than his personality were his legal troubles, and calling this an attempt to concisely explain them feels like an overstatement. There’s more to expect from the Post-Democrat on this later on, but hopefully this can clear up the misunderstandings in some capacity.

A Dying Breed of Hoosier Politics

His father, Daniel D. Dale, was the child of pioneer settlers in White County, Indiana, and a Civil War veteran. A Union Democrat and attorney, he additionally once served as an editor for Monticello’s The Constitutionalist. He married Ophelia Reynolds and the pair had four kids (Charles, George, Bertha, and Ida). George was the second oldest, born on February 5th, 1867. Less than a handful of copies of the newspaper have survived, and the local politics of Monticello are only scarcely recorded, so only so much can be said about this aspect of George’s childhood. Four page weeklies were the norm across the Hoosier state starting in the 1850s, and by the 1880s only the largest of townships could ever produce dailies. Telegraphic dispatches were a driving force for the town papers, which couldn’t get access to national or international news otherwise.1

There couldn’t have been any event in close second explaining what motivated his future editorials. Several people who had taken a jab at telling the story of Dale have said the same, including one writer from the Consolidated Press who stated that Dale “belongs to a dying race– the old-time weekly newspaper editor. He is redolent of printers’ ink, and he thinks more of the newspaper as an agency of reform than as an agency for producing wealth.”7 But his motivation to go against the grain in his writing took decades to accomplish, because from what is available from his early career, Dale appeared to be more exemplary than extraordinary. While managing to build up an image as relentless and vulgar in his writings already, he was still sharpening his pencil so to speak, and fell into the trap of following party loyalty before the risk of financial failure.

His start in journalism was a result of, once again, hating the repetition of his job, this time being his uncle Albert’s papermill in Hartford City, and deciding to start the Hartford City Press. But he remained living in the town on and off again between 1888 and 1915, started a series of local papers prioritizing a fight against bootlegging, and in his early 20s even served for a year as town clerk.8 He married his wife Lena Moler in 1900, who had a mostly unrealized role in his final paper, and they had a total of seven kids born up until the early ’20s.

But settling into a family didn’t slow him down. He was finding his footing where his father Daniel likely never went. In 1910, another local editor was put on trial for unwed sex with a woman in an interurban hotel, charged with improper conduct. Justice James Lucas read aloud every detail of the affair, infuriating not only to the defendant but to Dale, who stood up from his seat ready to trade blows. We only know from newspaper accounts that he used a “vile” name against the court, so it’s up to the imagination which one of his signature insults he managed to hurtle. But before getting thrown out he did manage to provoke Justice Lucas into charging towards him from the bench, and the infamous ordeal had to be split up by a deputy sheriff along with friends of Dales.9

1915 was the year he sold his last paper, the Hartford City Journal, and there awaited Muncie…

Nerves and Peril

Like any decade, or singular bygone movement, the twenties as a whole has been excessively mythologized. The decade retrospectively has been illustrated as a time only of flappers or jazz cigars, things that only tell us of a period where everyone’s life was cosmopolitan and liberated, or “revolutionary and bizarre” as Roderick Nash characterized it.10 This did in fact happen, and there was no shortage of this phenomenon in Muncie, which gained its status as a second-class city by 1921 and was even nicknamed “Little Chicago”, though simultaneously the general public reacted to those years by clinging to the very opposite impulse. For one, it was an irrational backlash to social change, but a result from living at the cusp of the interwar period. The end of WW1 caused disillusionment over what the future would entail, or, a “nervous epidemic.”11

What this meant for Muncie in 1915 would decidedly be a time of immense political turmoil. The last Republican mayor at that point was Leonidas Guthrie (1906-1910), whose term was largely a failure that oversaw the Street Car Riot of 1908, the Goddard Warehouse Fire of 1907,12 and an unpopular prohibitionist stance held by him and his party. Holding their opposition as wets, Democrats hit their landslide years first by electing Edward Tuhey in 1909 followed by Rollin Bunch in 1913. Two years after this win for Bunch, the newly emergent political boss of Muncie, he invited Dale to be an editor for his new political organ, The Muncie Post.

But a fallout took place between Dale and Bunch not long after, causing the Post to fold in early 1918.13 Mayor Bunch faced numerous political scandals after his reelection, with charges not limited to hiring an assassin to bomb the house of an opponent. Dale at one point had to testify against deputy prosecutor Gene Williams, a Bunch affiliate charged with soliciting and accepting bribes, who told Dale to secure for him a letterhead of the Civic League to make fake letters for evidence.14 But what did Bunch and his crew in officially was a mail fraud scandal in 1919, landing the Mayor in an Atlanta prison for eight months.15

When we plunged into a new decade, one that was exceedingly delirious and frenzied, the new hand we were dealt with engraved itself onto every part of life. For our municipality, citizens could not make the demands they once could in the 1910s. Decisions like construction were limited only to the war effort, sanitation regulations were also restricted, and the only financial problems that could be addressed were the most dire.16 For Indiana, the option for municipally-owned utilities was no longer feasible and was now a matter up to poorly enforced state regulations. Additionally, civic groups like the Chamber of Commerce were enabled to take a lead that city governments could not. In other words, local decision making veered towards business interests.

Past this, just about everything cracked up. If Republicans reformists advocated for efficiency and professionalization in the 1910s, the same forces turned fully reactionary in the aftermath of WW1. Though the same aforementioned reforms also extended to calls for “Americanization” and “social hygiene,”17 which had nativist and racist connotations. And thus the social order they would be calling for in the next decade was a natural culmination of this. As political factions of the Democratic party in Muncie were ostensibly the Bunch machine versus the incredulously vocal Dale, the landslide years of the party came to a close as Republicans took control of the mayors seat and city council in 1922. After a hiatus from writing, Dale had returned to it in 1921 and represented his views in his new offshoot paper, The Muncie Post-Democrat.

"Strange Things Are Happening In Muncie"

The aforementioned corruption scandals played a role not only in giving credit to an economic platform to the right of Dale’s party, but moreover to the nervous nativism espoused by those same big business advocates. In the eyes of such Klansmen, Dale wasn’t only a loud mouth threat, but a misguided crackpot to their high esteem.18 And while many individuals leading the Indiana Klan fit into categories of the uneducated and ignorant, the Klan had support from a wealthy, affluent, even respected upper class. Namely in Muncie, this would be the Kitselman family and even the prominent Ball family.19 This goes against what was called the “urban-rural thesis,” insisting that agrarian farmers felt status anxiety over the growth of urban cities, and decidedly lashed out.20 And even against connections made by historians between the Klan and 1890s populism.

The organizing of the Klan in Muncie was overshadowed in the local news by a city election that same year, which the Post-Democrat focused profusely on. As a loyal Democrat he endorsed Bunch early on, and yet his feelings of betrayal led him to ardently criticizing and exposing the candidate, and seemingly agreeing more with Republican’s calls for ending corruption and enacting law and order. But the following year, noise spread quick. If such a takeover of the community hadn’t been exposed yet, it was felt in the air all the same. Any of their calls for genuine reform (e.g. clean government to fight off a spoils system) were manifesting into absolutist mindsets with violence as a quick answer.

“In the eyes of such Klansmen, Dale wasn’t only a loud mouth threat, but a misguided crackpot to their high esteem.”

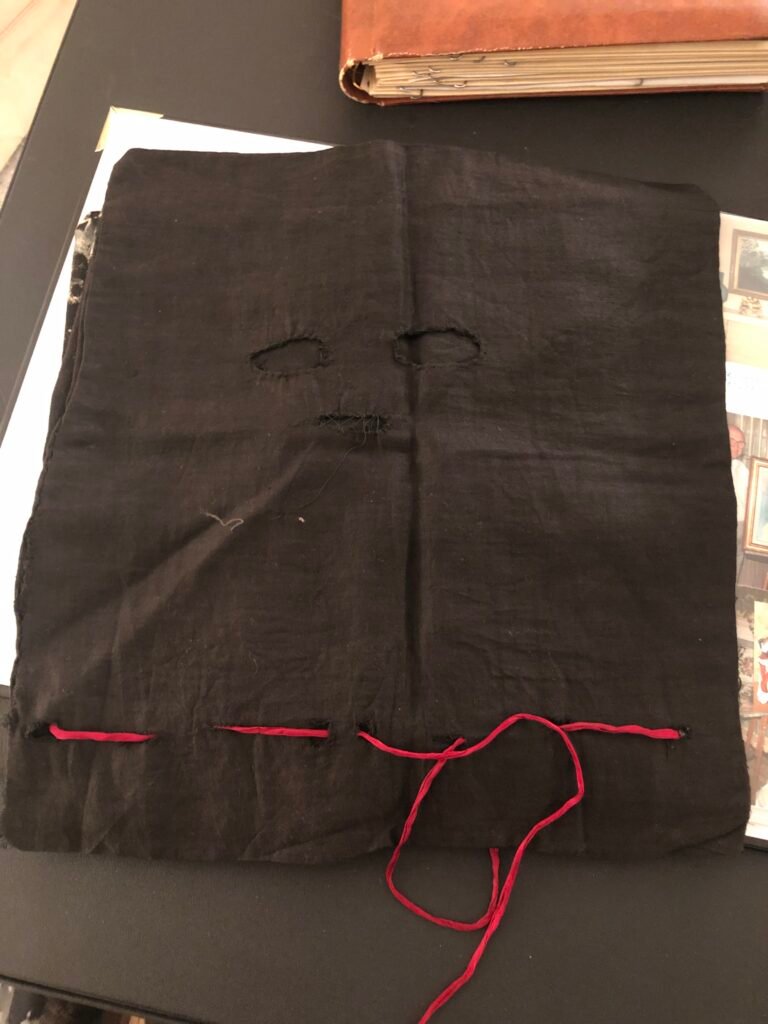

On March 24th, 1922, Dale and his oldest son Bud were attacked in the family home by bandits in black masks. Roughly at 10:30pm, two cars stopped at their home on Mulberry street, the masked men broke in, and one pointed a handgun on Dale’s ribcage. Dale immediately wrestled the revolver away from him and shot him in that moment. His son was attacked then chased out by another bandit. What provoked this attack, according to Dale, was one of his own editorials that same morning. The next week, Dale described the whole event and extended his rage onto the tone deaf city officials and their terrible handling of the situation:

“The Post-Democrat does not intend to be throttled by fear of personal violence. It will continue to tell the truth about the activities of crooked politicians and their lawless understrappers, in spite of the terror program which seems to have been

inaugurated in Muncie. Citizens who believe in law and order, and who do not want to see the city turned to scoundrelly Apaches with masks over their faces and murder in their hearts, should stand behind the Post-Democrat in its efforts to promote decent government and expose crooked politics.”21

The summer of ’22 was when the presence of the Ku Klux Klan became blaringly obvious. It was in June when a Black man named Robert Bledsoe was kidnapped and beaten also by men in black masks, and city attorney Clarence Benadum was quick to deny any connection of the incident with the Klan.22 Yet Benadum himself was affiliated not only with the Klan, but with the Mussolini-inspired Silver Shirts a decade later.23 In one case, when a march took place in that summer, then-Chief of Police Van Bendow went against orders to keep the streets open in order to prevent the Klan rally, soon removed from his position as a result. Three days later mayor Quick was pressured to reinstate him, proving the kind of influence the Klan had locally.24 Later that year on September 6th, prominent Klansman Edward Young Clarke spoke to a crowd in McCulloch park to exclaim that the organization “stood unequivocally for the perpetual control of America by the white race… not by might, but by right.”25

Dale’s Post-Democrat, finding its calling, reached thousands of copies sold per week by the end of the fall season for going after the Klan, hugely with the aim to satirize and mock the titles chosen and the rituals performed. He was set with the determination that even if a dozen robed members circled him into an inescapable corner, he couldn’t be subdued from asking the Kluckers why they get off on wearing their wives’ nighties. There was no telling where he would stop.

A known member Judge Clarence Dearth once said that he supported a newly proposed law that would sterilize the “feebleminded.” Dale sarcastically said in his paper that he agreed with the judge because if that policy were enacted one generation ago, there wouldn’t be a Ku Klux Klan.26 Another time he was charged with libel for calling a Klansman “100 percent a draft dodger,” an incident which started a continuously delayed legal case as so many of the legal woes played out.27 As other anti-Klan papers at the time performed, such as Tolerance, the Post-Democrat went through the task of publishing any membership lists that they could feasibly get their hands on. Dale even had a role in exposing Imperial Empress Daisy Douglass Barr, whom he once referred to as the “prize gold digger of the Klan” for pocketing millions of dollars by selling robes to KKK members, and as a result of Dale’s reporting she lost her role as chaplain of the Indiana War Mothers.28

For his stance against bootlegging, he notably didn’t hold back at the hypocrisy of leaders who drank despite their avowed support of prohibition. Imperial Wizard Edward Young Clarke had a quart whiskey bottle found in his car while giving a speech at McCulloch park, and in the next weekly issue Dale called Clarke the biggest fraud and hypocrite in America.29 Dale at this point, who could no longer be seen as an ineffective humorist but a real threat to their existence, was tossed several legal challenges just in the winter and spring of 1923 alone. It became clear that these were never sincere on the part of the Koo Koos, but only to intimidate him to give up his pen once and for all.

The threats were nonetheless substantial on both him and his family, and in November of ’22 Dale attempted applying for a gun permit and was eagerly granted one by the chief of police. Yet shortly thereafter he got arrested for carrying despite the permission granted.30 The permit was a set up, and he was convicted and fined $90 two years later.31 This was only the beginning of the war against the Post-Democrat, leading Dale to be thrown in the Delaware County jail so often that inmates would applaud him every time. While Dale was conducting an interview in the office of a lawyer, police burst into the room, searched for liquor, and despite no findings he was indicted.32

The charge itself was dismissed the following year, but in the process Dale faced an indirect contempt charge for an editorial from March 2nd, 1923 where he called accused Judge Clarence Dearth of being a Klansman and stacking juries with other members.33 For the trial of the same contempt charge, he submitted the original editorial itself as evidence, pissing off Judge Clarence Dearth who told Dale “if you don’t like it in Muncie why don’t you move to Russia?”34 The very act of using the editorial as defense was then used for a direct contempt charge, after he was sent to jail for making the defense, released on an appeal bond of $2,500, and subsequently given another ninety-day sentence and a fine of $500.35 Years of a single legal battle followed the direct contempt charge, not stopping Dale the same timeframe from writing “the Ku Klux Klan is a lawless, felonious, hypocritical gang of night-riding murderous outlaws.”36

The downfall of the Klan, or the 1920s wave more accurately, was starting to show its signs of degrade year by year. In a parade in June of 1923, citizens were physically attacked on the sidewalks for the rude act of not tipping their hats as the march came through.37 The upper class members were starting to leave from this point forward, and, in the middle of the same year, the Indiana Bar Association voted to condemn the Klan.38 It seemed as though the “best citizens” it was comprised of and the prestige of the fraternal orders was dwindling.

1925 was the blast that manhandled the fraternal order. Habitually written about, covered anywhere from decades-old biographies to Timothy Egan’s book last year, there was the downfall of Grand Dragon D.C. Stephenson. If the hypocrisy surrounding the booze-consumed Klan leaders was showing by this point, then the horrid treatment of women by Stephenson brought their grotesque nature to the public eye officially. His stenographer Madge Oberholtzer was kidnapped and raped by the Grand Dragon, leading to her attempted suicide and a subsequently fatal infection, caused by the bite marks left by Stephenson.39 Oberholtzer’s account of the events was posthumously released by the family lawyer and used to bring Stephenson to trial.

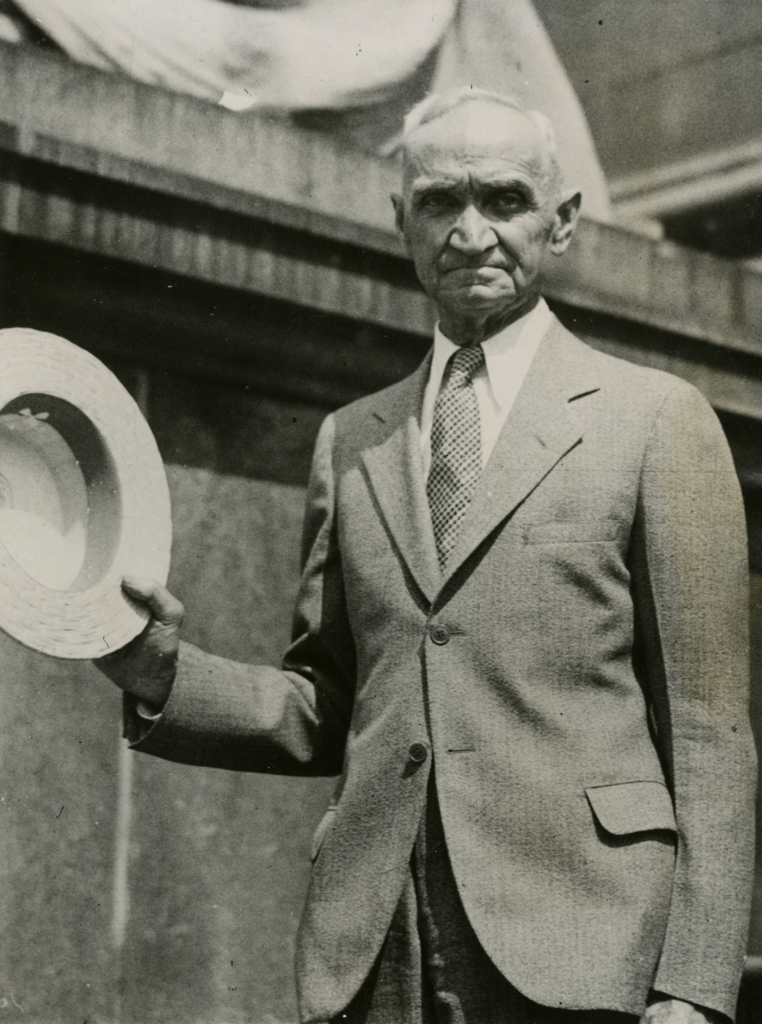

Dale was at that trial. Writer W.A.S. Douglass from the American Mercury described the editor as “a shabby little old man, a pencil in one hand, a wad of paper in the other, eternally scribbling while a pair of piercing black eyes under shaggy white hair seemed to be boring their way right through Steve’s brain.”40 The Grand Dragon’s smirk, which he held onto to assure himself the Klan-controlled legal apparatus could get him out of this, nearly fell off when he saw the editor he just couldn’t scab off. Dale managed to slip a note to the bailiff, who passed it to Stephenson that read “though the mills of the gods grind slowly, yet they grind.”41

The following year the Indianapolis Times won a Pulitzer Prize for exposing members of the Klan, something already done by The Post-Democrat, Tolerance, and many Black and Catholic-run outlets in years before. Though people like Dale didn’t go unappreciated…

Vindication

The nationwide storm of attention brought to the Klan’s fall carried through the decade. Though his editorials now focused on street contract grafting, in which contractors had done illegal bidding on city street paving jobs.42 It was a testament to his dedication to the local issues at hand, something he grew up in the crux of thanks to his father. Even with the notoriety he was starting to receive for his cunning attacks on the Invisible Empire, the Post-Democrat’s aim at the municipal level was the objective. And Muncie was quick to see him through on this issue, as more locals were going to public works meetings and the Evening Press reporter Wilbur Sutton was now following the story.

The contempt case that started in 1923, still revamping itself for all of these years, went to the Supreme Court of Indiana in July of 1926. It was there that Judge Julius C. Travis wrote in the opinion that “the truth is no defense,”43 and because of the ruling against Dale he would once again have to go to prison (notably at the State Penal Farm where he was also ordered to stay by Judge Dearth before). After just nine days, to the surprise of many, Governor and Klansman Ed Jackson issued a pardon. Dale wanted to bring the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, who denied taking up the case, but before they did he managed to receive donations from journalists around the country who were eager to defend freedom of press. Articles promoting the cause were being published by the Literary Digest, Chicago Tribune, New York World, and the New York Times.

Also in that year was another attack on the family home, with bullets fired inches away from Jack Dale, the youngest son. But as opposed to the situation almost a handful of years before, where city officials didn’t take the threats seriously, this time Attorney General Arthur Gullion sent a letter to the mayor and chief of police, telling them to protect the Dale house from more violent assaults.44 There was also Dale’s brief run for Indiana governor in 1928, a race which only constitutes a footnote compared to another election in just the next year…

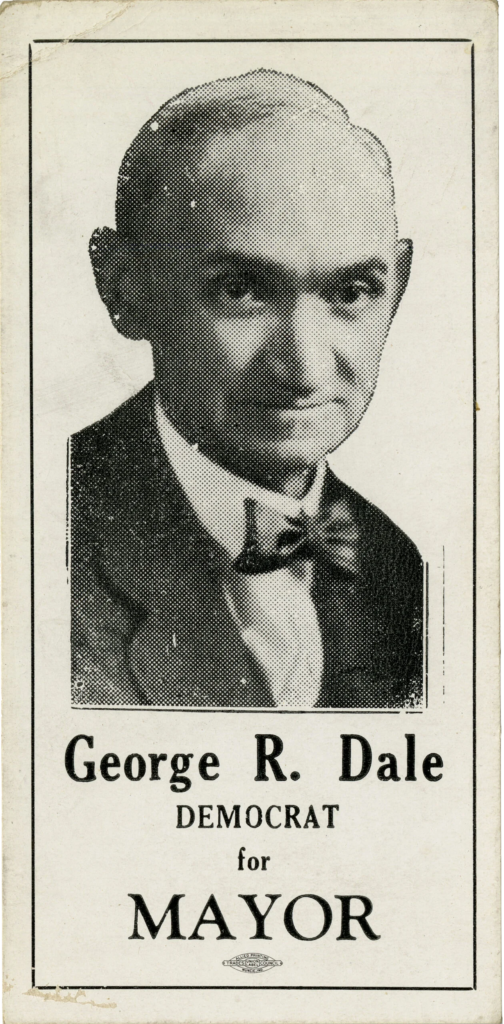

“George R. Dale Democrat for Mayor.” From the Personal Collection of Daisy Dale.

On March 11th, 1929, Dale filed as a mayoral candidate in the Democratic primary. Although he only won the primary by 158 votes, precinct total maps show that he won slim majorities in each Southside precinct and even much of the Northside.45 The platform was all his own. Like his own political persuasion, it fell between the class interests for the poor people of Muncie and aspects of middle-class reform. Not to mention appealing to voters with law and order, making the same calls he had been making for years prior through his newspaper. His platform called for city-owned utilities, something of a growing movement throughout the Hoosier state, as well as his continued fight against the “paving trust” and advocating for a merit system for the police and fire departments.46

His rival was Robert D. Barnes, a business man who received donations from the Ball family and local bankers.47 In terms of how much personal funding was used by both candidates, Dale spent almost twice as much as his opponent Barnes as opposed to receiving heavy donations. Almost a third was spent on radio broadcasts alone, and even more on political committee contributions. On election night the Northside results, typically Republican dominated, were astonishingly close with Barnes only winning that set of precincts with 4,552 to Dales 3,939.48 City-wide it was Barnes at 7,378 to Dale’s 8,727.49 Dale earlier on predicted that he would win by 2,500 votes, but some believed that he was just as surprised as his many rivals that he won at all. Dale would be inaugurated in January 1930.

Mayoral Years

Without even the remotest amount of hesitation, his first act as mayor was to fire every member of the police force. Because of his distrust in the department that he believed only served corrupt forces, the thirty-nine members were asked to give their resignations on the same day he was inaugurated.50 The new force consisted of Frank Massey as chief, and multiple anti-Klan cops who were fired during the Quick administration.51 The police force notably had grown to sixty-one members by the end of his term. Fearful over the prospect of legal battles designed to push him out of office, he appointed some of his own relatives into his administration (namely his son-in-law Lester Holloway, who later served as mayor in the late ’40s). He was quick to explain the decision in the Post-Democrat, which was still running while he was in office, though criticism over nepotism was still printed in the daily papers.

A failure of his administration was to acquire public utilities, receiving 2,683 votes in a petition, but the Central Indiana Gas Company scrutinized the effort out of existence.52 The only saving grace was that in 1933, Governor Paul V. McNutt reorganized the Public Service Commission, a commission which did a poor job at regulating utility companies in years prior, thus there was a better chance for new appointees to fight off the companies.53

In terms of parks, he decided to rename Northside Park to be dedicated to former mayor Edward Tuhey, who died in during Dale’s term in 1933. The following year of his proclamation, and by means of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, Tuhey Pool was built in the park and opened on July 15th, 1934.54

A Frame-Up

The new composition was majority Democrat, a fact that didn’t stop frequent clashes between Dale and its members. Councilman Harry Kleinfelder was his most consistent supporter, but out of thirteen total members Dale had less than a handful to count on. And, his seat was practically hanging off of a cliff for nearly the entirety of the term.

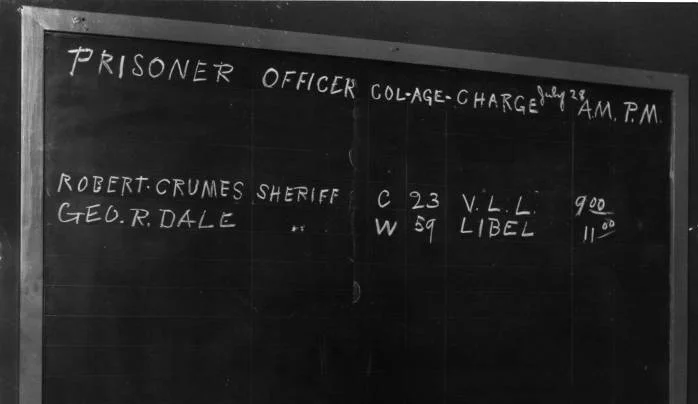

George, his son, and several others, were on their way to a Democratic convention, when they were stopped by state police and charged with possession of liquor.55 Not only were frame-ups like this done constantly to him in the Klan years, but he also had a record as a staunch dry going back to his years in Hartford City. And so he continued to hold that the people framing him were the bootleggers of Muncie whom he so upset for stopping their operations.

All during the same weekend, Dale was put in the county jail (a not so unfamiliar place to him), transferred to Marion County jail in Indianapolis, and released on a $10,000 bond by Monday.56 His arraignment took place March 17th, where he plead not guilty.57 He was indicted by a federal grand jury in Indianapolis and went to federal trial on May 16th.58 22 charges were made against the defense. One witness admitted that he had been hired by the city council to find dirt on Dale.59 At one point in the trial it was claimed that Dale was having an affair with the wife of a police sergeant.60 Days later on the 20th, he was found guilty of conspiracy to violate national prohibition.61

On June 3rd he was given an eighteen-month sentence and $1,000 fine, though released on bond within a week.62 The daily papers called for his resignation, justified with the Tucker Law in Indiana preventing individuals with a jail sentence of six months or more from holding public office. Though the same act didn’t stop Rollin Bunch from running in 1921. Still, Dale’s opponents wanted to use the law against him to force him out of office.63 In a last minute special meeting, city council passed two resolutions, one declaring Dale ineligible to hold office, and a second declaring City Controller Lester Holloway disqualified as well.64 Both Dale and his son-in-law filed appeals in Delaware County Superior Court declaring that the councils actions were illegal as they were not informed of the meeting, which at best prevented action being taken for a few months. October 4th was the date set for council to appoint a new mayor, however Judge Leonidas Guthrie (yes, the former mayor) issued an order stating that the council was out of reach from doing so.65

With the resolution declaring him ineligible to serve, the pressure to get a new mayor appointed, and postponements due to his poor health, everything carried on until August of 1933, when the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago ruled that there was sufficient evidence for the conviction that started this to be upheld.66 This helped for him to receive not a rehearing, but ninety days to prepare it for the Supreme Court.67 And with that, Dale had succeeded in getting this whole ordeal delayed for the final victory in this fight…

There was enough evidence of his innocence, specifically that there was perjury in the case, that President Franklin D. Roosevelt pardoned him in December of 1933, after being persuaded by Hoosier members of Congress a few months prior.68 Dale was given the news while getting his left eye treated in Maryland, where he quickly realized this meant his volatile status as mayor was out of the picture.

Though even with the notoriety, the whole event destroyed Dale’s chances at getting anything done. His only real moment of luck in the entire term was a decision by Governor Paul V. McNutt to sign a skip-election law, one of only two ever passed in Indiana, that delayed all local elections by another year. The logic was that passing such a law would save money for taxpayers, as the local election would now be the same year as the midterm, though the political incentive to do it wouldn’t be any surprise.

Now in his late ’60s, his relentless energy diminished. He campaigned for reelection and was primaried by thousands of votes that went for Rollin Bunch, who jumped out from his own political exile to return for a third term the following year, after also beating Republican opponent John Hampton in the general election. An ill George R. Dale continued writing for the remainder of his life after that term, from 1935 to the spring of ’36. His death was met with probably the most flattering and lengthiest piece about him in the Evening Press, and other obituaries by the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, and Time Magazine.

A Stifled Legacy

Between the ’30s and ’40s a dissident faction of the Democratic party, with similar pro-labor stances as George, held its own in Muncie politics. There was even something of a revival of this in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s led by Jerry Thornburg and Steven Caldemeyer. In 1947 George’s son-in-law Lester Holloway was elected mayor, with the strong support of his wife Libby, and the Post-Democrat was continued by George’s wife Lena until the early ’50s. This was definitely an echo, but many things about Muncie would remain the same. Now, we experience the same repetition of either business interests or machine politics. Either the solemnly talked about privatization or that “last hurrah” of political patronage we saw in the Dennis Tyler administration.

Author Timothy Egan recently visited Ball State just last November. I was taken aback with the amount of time he dedicated talking about George, and moreover when he exclaimed that he should have a statue for his fight with the Klan. Other than a once-standing McCulloch Park Dam dedicated in his name, removed in 2019, he hasn’t had that kind of postmortem honor. Or, at least, it’s been mostly confined in academic writings. In the last half decade of diving into this part of my genealogy, and now broadened to a new reiteration of the Post-Democrat, it still remains a question whether we can ever expect more for Muncie. Whatever George would have advocated for without the continual legal charges, it’s still an unrealized idea.

Notes:

- Thornbrough, Emma Lou. “Indiana in the Civil War Era, 1850-1880.” Indiana Historical Bureau. Indianapolis, Indiana. pg. 681.

- n.a. 1936. “George R. Dale, Former Mayor, Dies.” Muncie Evening Press. 1, 15, 23. https://www.newspapers.com/image/248902077/.

- n.a. 1885.”A Dastardly Assault.” Monticello Herald. June 18th. https://www.newspapers.com/image/882052760/pg. 1.

- n.a. 1886.”A Sudden Call.” Monticello Herald. March 18th. https://www.newspapers.com/image/881936363/. .

- n.a. 1888. Ophelia Dale Obituary. March 1st, Monticello Herald. pg. 1. https://www.newspapers.com/image/882023588/

- Ibid.

- n.a. 1926. “A Fight For Freedom of Press.” Literary Digest. Volume 90, Issue 7, August 14th. pg. 9.

- Giel, Lawrence. 1967. “George R. Dale, Crusader for Free Speech and Free Press.” Ball State University. Muncie, Ind. pg. 2-3.

- n.a. 1910. “Lived As Husband and Wife For Half An Hour; But That Was Not Criminal.” Hartford Daily Times Gazette. pg. 1. Blackford County Historical Society. (view images 1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

- Nash, Roderick. “The Nervous Generation: American Thought, 1917-1930. Elephant Paperbacks, 1990. pg. 3.

- Nash, pg. 2. “The decade after the war was a time of heightened anxiety when intellectual guideposts were sorely needed and diligently sought. Many clung tightly to the familiar moorings of traditional customs and value. Others actively sought new ways of understanding and ordering their existence. Americans from 1917 to 1930 constituted a nervous generation, groping for what certainty they could find. The conception of this time as one of resigned cynicism and happy reveling leaves too much American thought and action unexplained to be satisfactory.”

- Hooten-Bivens, M. 1992. “Worthy of Their Esteem: The Mayoral Years of Leonidas A. Guthrie As Reported in the ‘Muncie Morning Star’, 1905-1910.” Available from Dissertations & Theses @ Ball State University; Proquest Dissertations & Theses Global. (303978023). Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/worthy-their-esteem-mayoral-years-leonidas/docview/303978023/se-2. pg. 83-102.

- Brief mentions of his status as a “former” editor in the Evening Press: n.a. 1918. “Old Officers Are Generally Retained For Coming Term.” Muncie Evening Press. January 7th. pg. 1, 10. https://www.newspapers.com/image/249164319/; n.a. 1918. “It Is Now Up To Councilmen Whether Jobs Will Be Made.” Muncie Evening Press. January 10th. https://www.newspapers.com/image/249164346/.

- n.a. 1916. “Letter Writer Is Uncovered.” Anderson Herald. June, 3rd. https://www.newspapers.com/image/974358613/

- Buchanan, Thomas W. 1992. “The Life of Rollin ‘Doc’ Bunch, The Boss of Middletown.” Available from Dissertations & Theses @ Ball State University; ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/docview/303988116?sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses. pg. 92-109.

- Griffith, Ernest S. “A History of American City Government: The Progressive Years and Their Aftermath, 1900-1920. Washington, D.C. 1974. pg. 263.

- Gerstle, Gary. “The Protean Character of American Liberalism.” The American Historical Review 99, no. 4 (1994): 1043–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/2168769. Gerstle, pg. 1044

- Caldemeyer, Steven R. “The Legal Problems of a Liberal in Middletown during the 1920’s.” Ball State University. Muncie, Ind. 1970. pg. 3.

- Lynd, Robert Staughton. Lynd, Helen. 1924. Harold Hobbs Jr. interview note. December, 17th. Robert Staughton Lynd and Helen Merrell Lynd Papers. Ku Klux Klan (two folders). Box 9 Reel 5-6. (image here). As for the Kitselman family it is briefly mentioned here.

- Eagles, Charles W. “Urban-Rural Conflict in the 1920s: A Historiographical Assessment.” The Historian 49, no. 1 (1986): 26–48. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24446743.

- Dale, George R. 1922. “Assassins In Black Masks.” Muncie Post-Democrat. March, 31st. pg. 1.https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=d&d=BALLMPD19220331-01&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——-

- Schwartz, Martin D. “Unrest in Middletown: A Study in Municipal Pressures.” Harvard. 1938. pg. 32.

- Ibid

- Giel, pg. 19.

- n.a. 1922. “Thousands Hear Ku Klux Leader.” The Morning Star. September 7th. https://www.newspapers.com/image/251426949/

- Dale, George, R. 1925. Untitled. The Muncie Post-Democrat. January 27th. pg. 2. https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=d&d=BALLMPD19250227-01.1.2&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——-

- Dale, George, R. “Extra! Extra! Editor On Trial Again.” The Muncie Post-Democrat. January, 18th. pg. 2. https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=d&d=BALLMPD19240118-01.1.1&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——-

- Taylor, Stephen J. 2015. “‘Koo Koo Side Lights’: George Dale Vs. The Klan.” Hoosier Chronicle. December, 17th. https://blog.newspapers.library.in.gov/koo-koo-side-lights-george-dale-vs-the-klan/.

- Dale, George R. 1922. “Boss Wizard Clarke, Wife Deserter, and Degenerate, Faces Federal Liquor Charge.” September, 8th. pg. 1. https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=d&d=BALLMPD19220908-01.1.1&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——-

- Schwartz, pg. 74.

- Caldemeyer, 25.

- Giel, pg. 30.

- Smith, Ron F. 2010. “The Klan’s Retribution Against an Indiana Editor: A Reconsideration”. Indiana Magazine of History, December. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/article/view/12574. pg. 382.

- Giel, pg. 32

- Ibid, pg. 32.

- Dale, George R. “It Is Someone’s Business.” The Muncie Post-Democrat. https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=d&d=BALLMPD19230601-01&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——- pg. 2

- Smith, 392.

- Giel, pg. 36.

- Egan, Timothy. 2023. “A Fever In The Heartland: The Ku Klux Klan’s Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them.” Penguin Random House. pg. 193-233.

- Douglas, W.A.S. 1930. “The Mayor of Middletown.” The American Mercury. pg. 479.

- Egan, pg. 270.

- Frank, Carrolyle. 1974. “Politics In Middletown: A Reconsideration of Municipal Government and Community Power in Muncie, Indiana, 1925-1935.” Ball State University. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/politics-middletown-reconsideration-municipal/docview/302747393/se-2. pg. 98-164; additionally we have an archived post about it at this link: https://munciepostdemocrat.com/index.php/history/elementor-1393/#PavingTrust

- Literary Digest, pg. 9.

- Gillion, Arthur L. 1926 “Letter from Arthur L. Gillion to Muncie Mayor and Chief of Police.” BSU DMR. December, 6th. https://dmr.bsu.edu/digital/collection/DlGrgRCol/id/287/rec/3

- Moran, Thomas. 1978. “Pendulum Politics: The Political System of Muncie.” Ball State University. pg. 68.

- Ibid, pg. 68.

- Frank, pg. 244.

- Moran, pg. 68.

- Ibid, pg. 68.

- Frank, pg. 481-483.

- Ibid, pg. 481-483.

- Frank, pg. 640.

- Madison, James H. 1982. “Indiana Through Tradition and Change: a history of the Hoosier State and its people, 1920-1945. Indiana Historical Society pg. 239.

- Kelley, Brooklynn. “History of Tuhey Park.” muncieparks.com. n.d. https://muncieparks.com/history-of-tuhey-park/

- Frank, pg. 505.

- Ibid, pg. 506.

- Ibid, pg. 507.

- Ibid, pg. 512-513.

- Ibid, pg. 517.

- Ibid, pg. 518.

- Ibid, pg. 523.

- Ibid, pg. 524.

- Ibid, pg. 526.

- Ibid, pg. 532.

- Ibid, pg. 536.

- Ibid, pg. 558-559.

- Ibid, pg. 559.

- Ibid, pp. 559-560.